Advent of Code in Three Languages

Different programming languages push us to write code differently.

Python pushed me to write clean code.

Rust pushed me to write performant code.

Haskell pushed me to solve problems differently.

Three Borrowed Refs, Two Left Folds, & A Python In A Binary Tree

Every year, Advent of Code puts out 25 coding puzzles in December, one a day until Christmas.

I first did AoC in 2015, when I was just starting to seriously learn Python, coming from a scientific/statistical computing background in MATLAB and R.

Since then, I haven’t gone back to AoC. My Decembers were filled with writing papers, not code, and my free time was spent learning math, not programming.

This year I had some extra free time on my hands, so I decided to go back to Advent of Code.

And this time around, I decided to work through the problems

in three different languages:

Python,

Haskell, and

Rust.

I used replit

to get access to persistent, web-accessible environments

for all three languages in a unified interface.

Links to executable versions of my solutions, hosted on replit,

are sprinkled throughout this post.

You can find all of the solutions

here,

named XX - langName for XX in 01..08

and langName in Python, Rust, Haskell.

Python is a loosey-goosey language: it’s interpreted, dynamically-typed, and garbage-collected. Haskell is much less loose, but is even more abstract, in the sense of being far from the metal: it’s got a strong type system, works declaratively, and evaluates pure functions lazily. Neither language foregrounds performance or memory management, unlike Rust, a compiled systems programming language that uses borrow checking to make memory maintenance easier.

Before starting this process, I was deeply familiar with Python, at an early-intermediate level with Haskell, and completely new to Rust.

Working through the Advent of Code problems in three very different languages, each of which I have very different familiarity with, was an incredible educational experience. My knowledge of all three languages, and of programming in general, was greatly deepened.

This blog post summarizes what I learned from that experience, as best I can.

Here are my main tl;drs: two truisms about programming languages in general, plus the specifics for each language, and a note about using Advent of Code and puzzles to learn a language. After covering each of these in detail, with examples, I’ll closes out with some smaller take-aways about tooling.

Different programming languages push us to write code differently.

Python pushed me to write clean code.

Rust pushed me to write performant code.

Haskell pushed me to solve problems differently.

Each language has its strengths and weaknesses.

Python is easy (but slow).

Haskell is hard (but beautiful).

Rust is fast and easy to learn (but abstraction is hard).

Doing lots of puzzles quickly ingrained some bad habits.

I ended up copy-pasting lots of code, especially boilerplate.

I ended up writing lots of solutions that “just worked”.

Different programming languages push us to write code differently.

The basic version of this truism predates computers. There’s a possibly apocryphal quote, supposedly of Nietzsche, the late 19th-century German philosopher, on beginning to work with a typewriter:

As our minds are working on our tools, so our tools are working on our minds.

Programming languages are, alongside hardware and developer environments, among the core tools of a programmer, so they work very intensely on our minds. Their assumptions become our biases and their happy paths become our preferred routes.

Working on the same problems in three very different languages in short succession made this evident, but it also suggested ways to bring the strengths of each language into work done in the others.

Python pushed me to write clean code.

Python uses whitespace to organize code and does not require type declarations, so there’s a minimum of “cruft” around the core logic of your code.

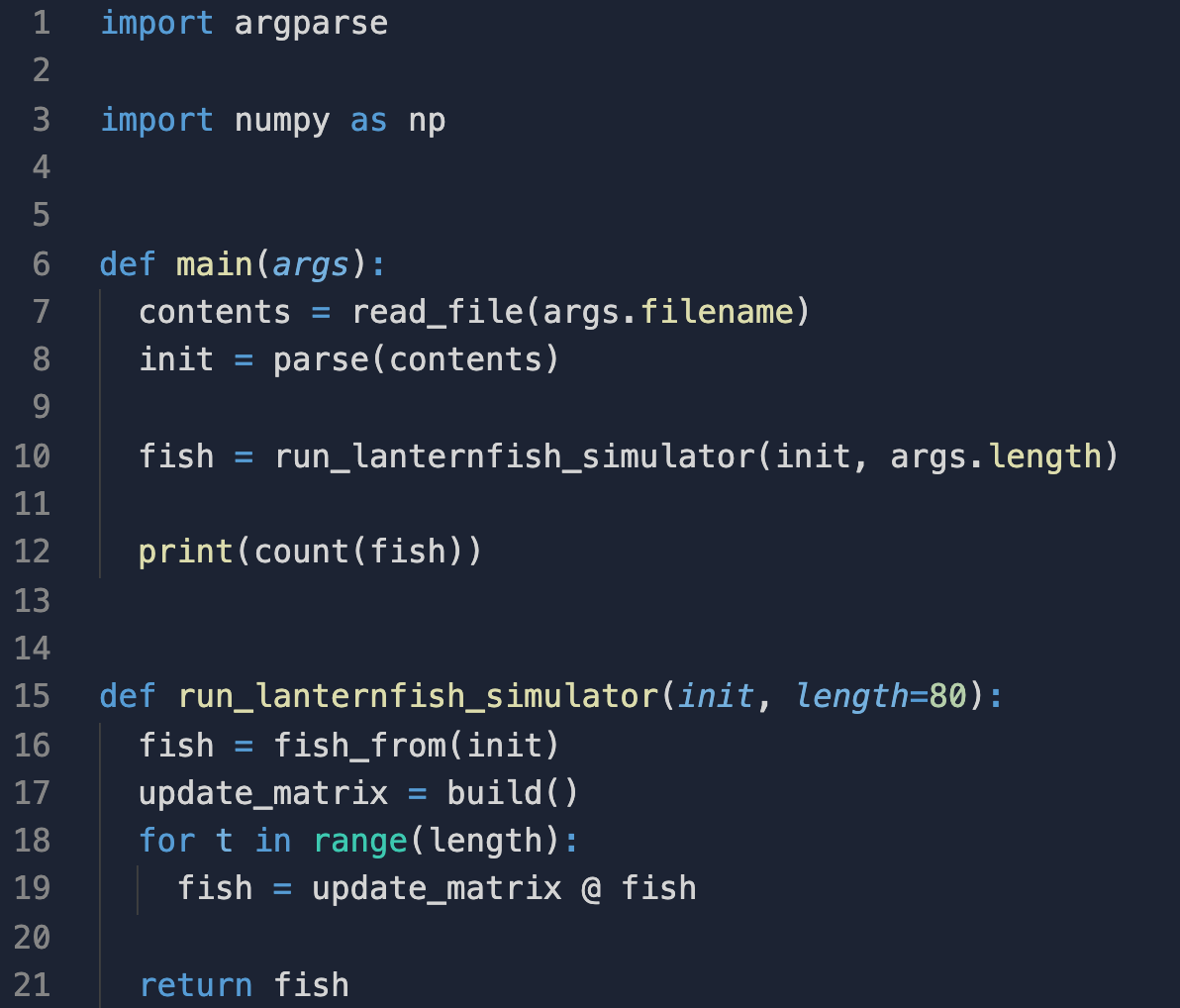

Consider this example, from my Python solution to Day 6. On Day 6, we’re asked to simulate the population growth of lanternfish.

The instructions of the main function read almost

like a prose description of (or at least pseudocode for) the program:

readafile,parsethecontents,- then

runthelanternfish_simulatorand countthe fish up.

In the absence of visual distractors, like brackets or variable annotations like type and mutability, the source code only contains the instructions we are giving the computer. For me, this encourages a “readability discipline”: I want the gist of the program to be as clear to a reader as the execution of it is to the computer.

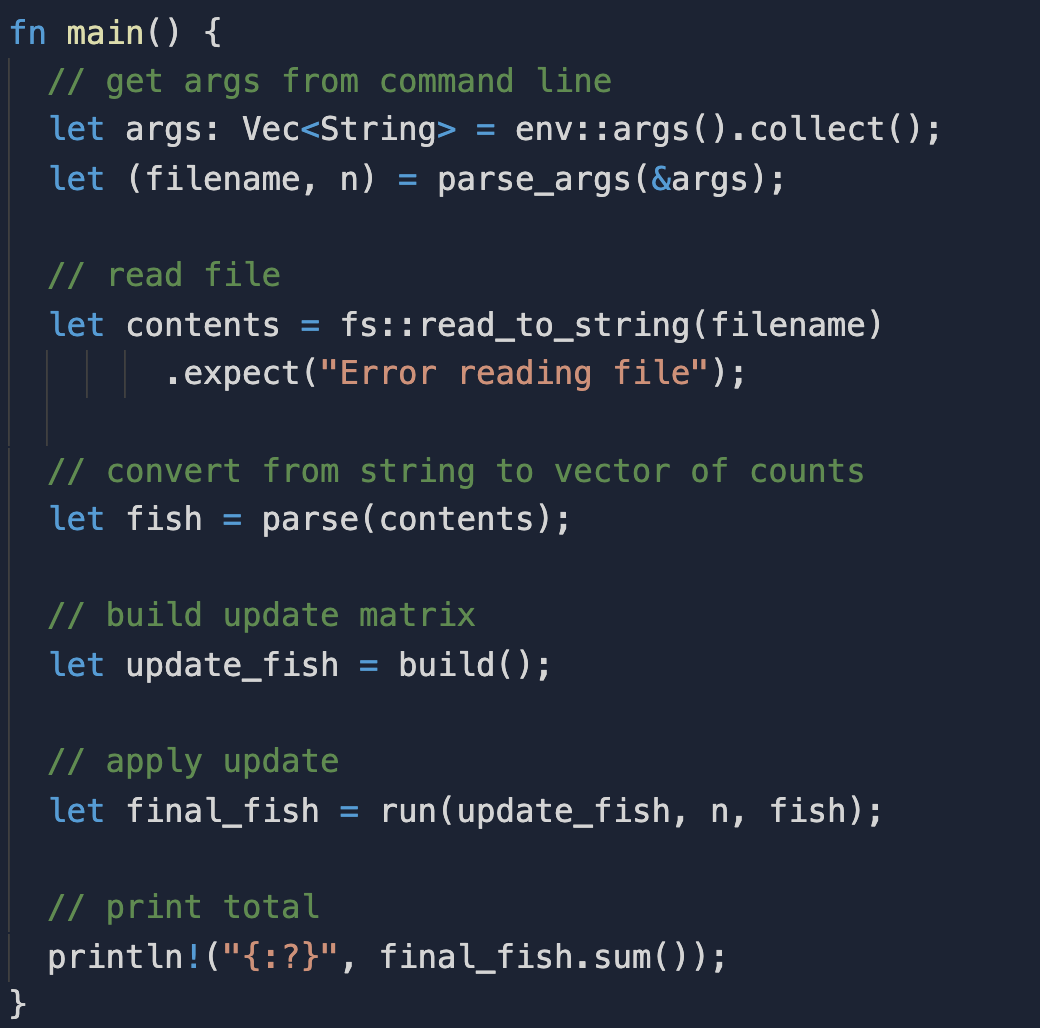

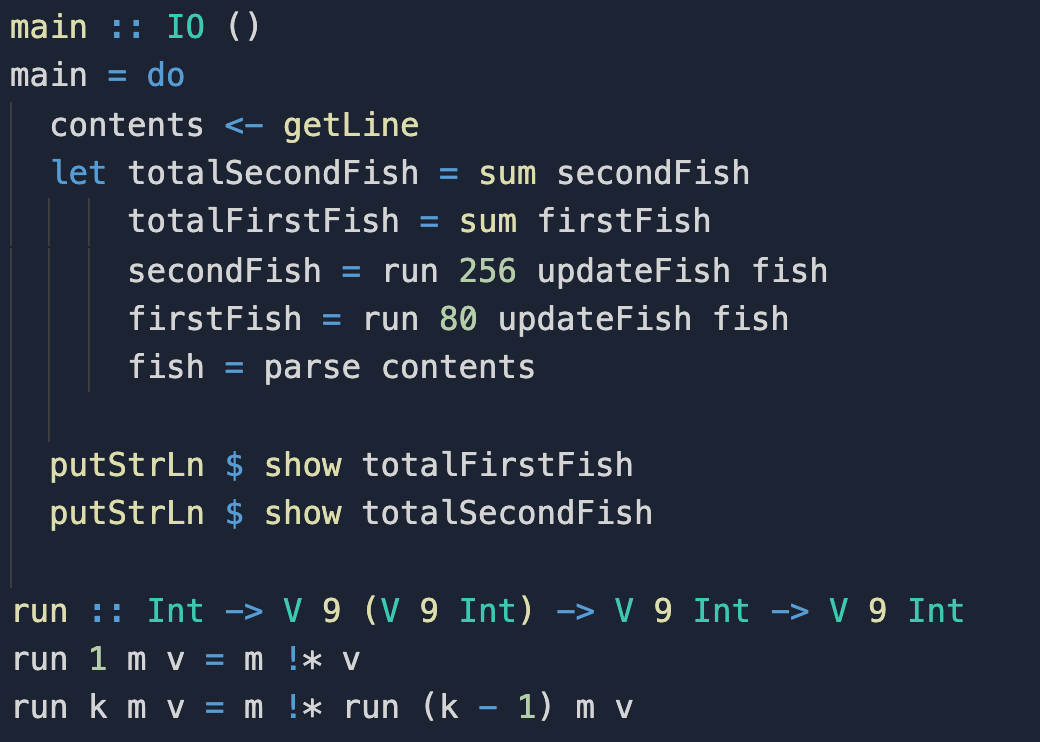

As I worked on my Rust and Haskell solutions,

I tried to maintain this discipline.

In Rust, I avoided manually inlining as much as I could,

so that the main function,

and the functions it calls directly, would be as short as possible.

In Haskell, I used let blocks to organize the calculations

in my programs, with clear and descriptive names for variables and functions.

This influence is clearly visible in the soltutions for the same day in Rust (executable source code on replit) and Haskell (executable source code on replit):

Rust pushed me to write performant code.

Rust, on the other hand, was constantly reminding me of the performance cost of my code: with every cloned value from the heap, every pass over an iterator, every additional layer of functional abstraction, I could feel that I was adding weight to my program.

Contrary to the “human-readability” bias I was absorbing from Python, Rust’s constant emphasis – in the type system, the syntax, and the standard library – on just exactly what the computer would be doing during execution encouraged me to try and make things simpler and easier from the computer’s perspective. If a function would only be called once, why not inline it and save the extra weight of borrowing or of specifying additional types?

Outside of specialized, highly performance-sensitive contexts, I think this is a bad instinct. But the instincts of Rust aren’t all bad. When turning to Python or Haskell from Rust, I found myself noticing more often when I was triggering an expensive operation like a copy or (especially in Python) iterating over a data structure more than once unnecessarily.

As a novice Rust programmer, I was particularly scared of functional abstraction, because it required more thoughtful and deep engagement with Rust concepts like borrowing, closures, and function types.

This experience couldn’t be more different from the experience of writing Haskell.

Haskell pushed me to solve problems differently.

Unlike Rust, functional abstraction is effortless in Haskell.

For example, currying, where a function of two arguments is transformed into a function of one argument is hard in Rust. Currying in Haskell is like water to fish: any “function of two arguments” in Haskell

f :: a -> b -> c

is actually a function of one argument that returns a function of one argument.

f :: a -> (b -> c)

So instead of working primarily by manipulating values, as in Rust and Python, Haskell encourages the programmer to manipulate functions. Solutions or levels of abstraction that would be fiendishly complex in an imperative, value-centric paradigm become simple and natural in a functional paradigm (and vice versa).

Because I learned programming imperatively (MATLAB, R, and Python), my first instinct on seeing a problem was to solve it in an imperative way: generating and mutating finite data structures.

With Haskell, I found that I needed completely different solutions. Advent of Code problems mostly involve taking a text file as input and producing a single number or string as output – this structural constraint makes it easier for the organizers to implement randomization of inputs for individual participants and to allow easy entry and checking of answers in a language-independent way.

From a Haskell perspective, that means all of the problems can be solved by composing two pieces:

- a parser that creates a data structure from the input and

- a catamorphism

that consumes the data structure and spits out the answer –

for the puzzles I completed, typically a

foldon a list.

Framing my solutions in this way often led to very different solutions in Haskell than in Rust or Python – some of which were better.

For example, on Day 7 we are asked to compute the cost-minimizing position for some submarines, which happen to be driven by crabs (Advent of Code is whimiscal like that). In my Rust and Python solutions, I immediately reached for arrays: calculate the cost for each position for each submarine (then sum up and find the min/argmin). This solution was \(O(n^2)\) – note the nested “for each”.

It’s perfectly feasible to program this solution in Haskell (probably as an indexed traversal), but it didn’t feel “natural”.

Looking more closely at the problem, it was clear that the functions being optimized were convex: they had only one “change of direction” from decreasing to increasing. This gives an \(O(n)\) algorithm: iteratively increase the starting position until the function stops decreasing.

While that sounds like a stateful algorithm,

which would not be particularly idiomatic Haskell,

it has a clean and terse functional equivalent:

apply drop to an infinite list of costs,

returning the first element whose successor is greater.

So that’s what I did in

my solution.

This completely different perspective on the problem both resulted from a deeper understanding of what I was doing and led to a speedup from quadratic to linear time complexity (and from quadratic to constant space complexity).

When working in the other languages, my thinking didn’t even come close to this solution. But importantly, once I found it, transferring this solution to Rust or Python would be straightforward.

Working with a language, like Haskell, that operates in a paradigm completely different to the norm is a great way to uncover totally different ways to solve problems – something much deeper than the cosmetic and optimization differences between working with Rust and Python.

Each language has its strengths and weaknesses.

This truism bears repeating if only because programmers often become chauvinists for their first language, or for the latest hotness, or for the time-worn and battle-tested: there is no one tool that is best for all jobs.

Tools that succeed succeed because they solve at least some problems well in some circumstances; tools that succeed are doomed to fail on at least some problems in some circumstance.

Python is easy (but slow).

First, I should admit I am biased: I am most comfortable in Python, which has for me been both an educational environment for learning programming concepts and fleshing out mathematical ideas and the high-level interface to quickly build numerical programs, from Markov Chain Monte Carlo for statistical computing to deep neural network training.

That said, Python just is easier than Rust or Haskell, for inherent and for cultural reasons:

- It’s easy to refactor, since there’s less text (e.g. type signatures, variable annotations, syntax) to change around.

- It’s easy to switch programming paradigms on the fly, since there’s good support inside the standard library for different programming paradigms.

- The language’s popularity and maturity mean there’s a plethora of libraries that include specialized data structures and algorithms, like this function from scipy that was essentially a one-line solution to Day 9.

- Similarly, that popularity and maturity mean that there’s also a plethora of high quality tutorials, blog posts, and Stack Overflow discussions where you can learn how to solve particular problems or use certain tools and libraries. I found myself particularly missing these resources when working in Haskell.

Of course, the flexibility and lack of rigor in the program specification also means it’s easier to write an incorrect Python program that still runs. I think one reason Python feels particularly easy to use for Advent of Code challenges is that they are a form of test-driven development. In the Platonic ideal of TDD, tests are written before code, and the code is finished when it passes the tests. That’s how Advent of Code works: the submission acts as a test, and the problem statements typically include lots of results to test your code against – all written down and then read by the programmer before any code hits a text file.

The other cost to this ease of use is execution speed. Consistently, the compiled Haskell and Rust programs would be effectively instantaneous – bound by printing to the terminal for a human to read the result, rather than by internal computation. Not so for Python, where there was often a slight but noticeable delay while the program executed.

Fundamentally, that’s because Python is interpreted rather than compiled, uses a garbage collector to manage memory, and has limited thread-wise parallelization. These are core language features that are very difficult to work around.

That makes Python unsuitable for a lot of domains. But for many problems, this speed difference is not a dealbreaker, just as it was not a dealbreaker for Advent of Code. When the Rust (and sometimes Haskell) programs would terminate in well under a second, the Python programs would terminate within a few seconds. For a program that only really needs to be run once, like these Advent of Code solutions, that’s an extremely tolerable cost; the same likely holds true for other applications, like running a job on a minutely/hourly/daily schedule.

Haskell is hard (but beautiful).

I’ve been learning Haskell on and off for a few years now. I’ve treated it as a way to learn more about category theory and abstract algebra than as a new programming language for solving concrete problems.

In that time, it has become easier to write Haskell programs, but I still find it challenging. In fact, even though I just started learning Rust within the last month, I often found it easier to write a Rust solution than a Haskell solution. I think there are two core reasons.

The lesser of the two reasons is that the dev tooling for Haskell is not great, compared to the tools for Python and Rust. See the Minor Take-Aways section at the end of this post for more on this.

The bigger reason is that Haskell is a declarative language, rather than an imperative language, and imperative languages are more “natural”.

They are more natural in two senses.

First, imperative languages are clearly closer to how a computer runs. At the core of a computer, registers that contain state are operated on to produce new states, in one step after another. This is imperative programming par excellence. The gap between declarative Haskell source code and the final imperative program (which is closed by the compiler) makes it very difficult to reason about some aspects of Haskell program behavior, as in the notorious space leaks that are caused by laziness.

Second, imperative languages are, more speculatively, closer to natural human thought. Human brains did not evolve to write proofs or programs; they evolved to maximize survival and reproduction in a world of prey, predators, and packmates. These are agents who take actions in an environment – statefulness, mutability, and time are first-class citizens. We express our thoughts in sentences that combine state (nouns) with action (verbs). This closer match between the structure of imperative programs (“do this, then that”) and the structure of our intuitive thought makes it easier for us to work with them.

Bartosz Milewski in his YouTube lecture series Category Theory for Programmers II, draws an illustrative analogy here, drawing from mathematical physics.

He likens imperative programming to the Hamiltonian approach to mechanics. Hamiltonians are used to derive differential equations that predict the motion and behavior of a system. A differential equation is like a imperative program: at each point in time, it gives an update to the value of a state, which is then used to update the state at the next point in time.

Declarative programming, on the other hand, is more like the

Lagrangian approach to mechanics.

Solving for the paths of systems in Lagrangian mechanics

is based on minimization:

the path a system follows is whichever one minimizes

a quantity called the action.

There is no obvious flow of time – the entire path

is solved for at once.

In English, you might declare “let the path be that which minimizes the action”;

in Haskell, this becomes let path = argmin action paths.

By the way: if you’re not well-versed in physics, the duality between the Hamiltonian and Lagrangian views of the world is both explained and dramatized beautifully by author Ted Chiang in his short story “Story of Your Life”, which was the basis for the 2016 movie Arrival.

Critically, these approaches are dual: every mechanical system admits a description from both viewpoints. From one, the other can be mechanically derived.

The derivation or transformation from a declarative, stateless form to an imperative, stateful form is precisely what the compiler or interpreter of a declarative language does – in the end, our computers have inherited our bias towards the imperative view.

So Haskell is hard – hard in a way that, to me at least, feels as fundamental as the structure of thought. But there are decided benefits to grappling with its challenges.

Almost every time I completed a solution in Haskell, I felt like I had understood something fundamental and deep about the problem I was solving – like in writing the program I had connected the specific problem to a broader class of problems or even learned something entirely new about computer programming.

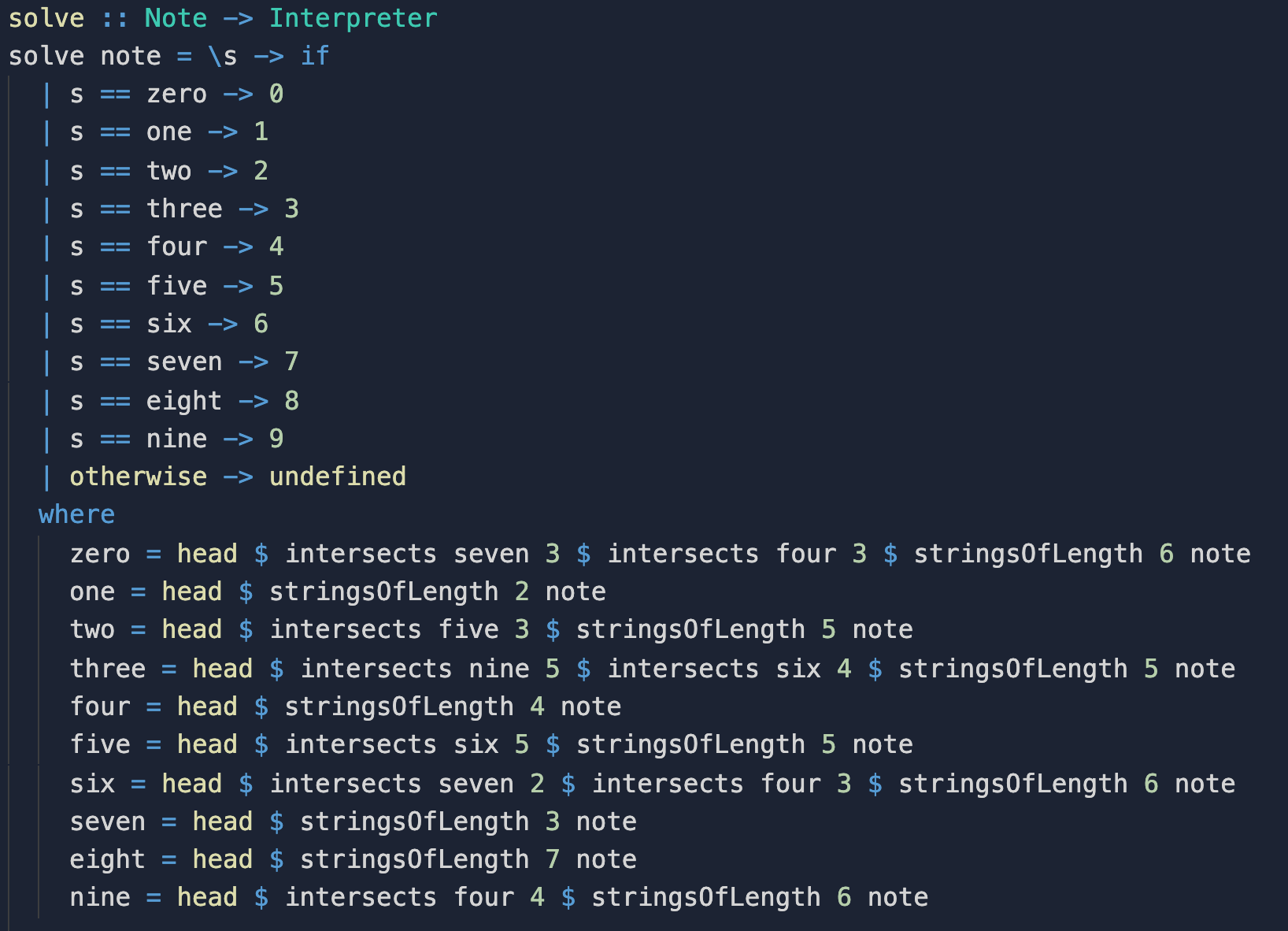

For example, on completing the seven-segment display challenge on Day 8 in Python, I felt frustrated – I had hacked together a solution that worked but had no deep explanation for why.

The core of the challenge is to match each of ten provided strings to a digit, based on the patterns of a seven-segment display (as on a digital alarm clock).

In Python, I used repeated iteration of a few heuristics to narrow down which string went with each digit.

When I tackled the question a second time, using Haskell, I had to take a completely different approach.

I was inspired, by an answer I found on Twitter, to effectively define each digit – declare which one it was – rather than worry about the procedure for calculating it.

This approach shows up in the where block in the code below.

For example, the string for the digit five is the one that intersects

that for the digit six 5 times (and is one of the stringsOfLength 5).

The identity of the string for the digit six is similarly defined.

Because of the lazy and declarative semantics of Haskell,

these values can be defined in totally different orders

in each execution –

when given one set of ten strings as input,

the identities of the digits might be solved in a completely different order

(first four, then nine; or first seven, then four, then zero, and so on).

All that matters is that the terms are properly defined, with no cyclical or missing definitions. When I translated this solution into Rust, I had to be precise about the order in which the solution had to be computed.

Lastly, because I was wrapping these solutions up into functions (the lambda term at the top of the screenshot above), the close connection between lambdas, closures, and data constructors for function types was made manifest: lambdas act like data constructors for function types, using currying to map a function defined on the pair of context and argument into a function that takes a context and returns a function that takes an argument – effectively closing over the context in which the lambda was defined.

In the end, this was a solution I was proud of and one from which I learned, rather than an ugly hack that made me feel frustrated.

That was my general experience with writing solutions in Haskell. Each one was a gem – transparently clear, austerely beautiful (to their mother), and hard-won by toil with pick and polish.

Rust is fast and easy to learn (but abstraction is hard).

As noted above, I only started learning Rust just before starting Advent of Code. After a month, I can already say it’s one of my favorite languages to write code in.

Despite being a systems programming language, Rust is easy to learn:

- The Rust By Example (RBE) document is one of the best ways to learn programming I’ve ever come across. It mixes clear and pedagogical exposition with links to reference documentation and (critically) editable, executable code. This executable code is backed by Web Assembly (Wasm), with which Rust plays very nicely. RBE demonstrates just how useful and powerful Wasm can be – and so also why one should learn Rust.

- The Rust compiler is actually your friend. Error messages from compilers and interpreters are notoriously arcane and useless. After a lot of exposure, I can just barely grok the output of the error messages from GHC, the primary Haskell compiler. The error messages in Python’s standard library are similarly less helpful than they could be. The Rust compiler, by contrast, typically gives extremely clear error messages that identify where in a line the error is and how to fix it, with links to additional detailed documentation. In conversation with the compiler, a novice in the language (like me) can take a very broken program, with errors in variable ownership, mutability, type matching, syntax, and more, and get it running.

- Rust clearly learns from other popular languages.

Much of the syntax and nomenclature echoes Python,

but without the unpopular significant whitespace.

The type system has shades of Haskell as well,

and Rust can also automatically

derivesome traits. As a systems language, it also draws heavily from C and C++. This makes it feel familiar from almost any programming background. - As the most-loved language on StackOverflow, Rust gets a lot of love on that platform, meaning there are lots of well-answered questions and accompanying code snippets.

And this is all while being blazing fast:

when compiling Rust programs in --release mode,

the results were uniformly extremely snappy.

There’s one drawback that I noticed: functional abstraction is not easy. It’s not exceedingly difficult to do maps and folds – you can get pretty far by passing basic functions or lambdas into iterator interfaces. Function types are needed to work seriously with higher-order functions, and these interact in a more complex way than I expected with the borrow checker. I found myself copying and pasting code I didn’t understand much more often, along with blindly following the compiler’s suggestions.

Doing lots of puzzles quickly ingrained some bad habits.

The quick pace and goal-orientation of the puzzles was good: it kept me moving, gave me clear feedback on success, and prevented me from spending too much time on abstraction.

But it also encouraged me to cut corners in ways that were harmful for learning.

I ended up copy-pasting lots of code, especially boilerplate.

In Haskell, I didn’t learn as much about monads and IO as I would’ve liked because I just used the same format for each program. I also didn’t learn how to do clean argument parsing. I also stuck with the fairly janky and unergonomic Haskell Cabal setup provided by replit without diving deeper into how it worked.

In Rust, I slapped together a barebones argument-parsing and file-reading approach on the first day and then copy-pasted it into subsequent solutions. In both cases, I didn’t come away with the knowledge required to write a clean CLI tool in the language.

For all three languages,

I settled on a basic bash script for running all the programs

in the first day or two, then didn’t improve it.

It would’ve been better to e.g. use make to reduce compilaton overhead

and look into more of replit’s features.

I ended up writing lots of solutions that “just worked”.

I initially set myself the goal of doing every puzzle in each of three languages. If I was really cooking, I could get a solution in Python in an hour or two, but it was more typical to take three to five.

There was a new puzzle each day, so I was looking at 8+ hours of coding daily to keep up. Even after cutting my target down to 1/3 of the puzzles in each language, I was still looking at multiple hours of coding every day.

This put pressure to “get stuff done” and “just ship it”, rather than take time to learn.

In Haskell, this meant that my refactoring was limited,

even though confident, safe refactoring from an MVP to a clean program

is one of the joys of that language.

I didn’t learn good “Safe Haskell” habits

(which is what most folks are thinking of when they say things like

“Haskell programs are guaranteed not to crash at runtime”).

I also didn’t learn about “Template Haskell”

for reducing boilerplate and

I only scratched the surface of Lenses

(pun and negative connotation intended).

In Rust, I never did a deep dive on ownership/borrowing, closures, or traits. I have no idea what a macro is or how I would make my own. Instead of looking into the reasoning for the compiler’s suggested fixes, I just blindly accepted them, and I likely tied my programs into knots while doing so.

In Python, I didn’t learn anything new – no new libraries or idioms. I also didn’t practice the hypermodern style.

Minor Take-Aways

Above were all the major take-aways.

I’ll close out with some smaller things I learned.

replit is great for prototyping.

replit provides persistent environments for development, with an emphasis on education and hobby programming.

It was straightforward to get set up with each language.

It required a moderate amount of boilerplate and copying each time (especially for Haskell, where tooling wasn’t as good), but nothing too excessive.

By the time I was really going with each language, though, I wished for the full control and automation tools that a more traditional environment would offer. If I do this next year, I’ll spend a day or two before the month starts setting up a nice development env with a makefile, nesting, etc., and use GitHub for hosting.

That said, it was wonderful to be able to setup envs quickly and access them from any device, with persistent storage. One issue I ran into: on a particularly poor internet connection (airplane WiFi, a phone tether), replit became unstable and I had to switch to using Google Colab, which was a decidedly worse experience outside of Python.

Tooling and libraries for Haskell are very limited, especially for linear algebra.

As you might expect for a more niche language, the tooling for Haskell is not great.

The Haskell Cabal replit template wasn’t great.

For example, it comes packaged with a setup of the cabal

built tool that requires a v1- prefix for all commands (cabal v1-build)

or else prints a warning.

There was also no real IDE integration in the editor.

There was no real syntax checking (outside of highlighting),

no type hinting or checking,

and no useful form of autocomplete.

But it’s not just replit’s fault. Haskell is not a broadly popular language, so there’s less of everything, even beyond tools: StackOverflow discussions, YouTube tutorials, code snippets, etc.

And unfortunately for folks interested in learning to use Haskell, the documentation for most libraries is poor, especially in comparison to Rust. I found myself looking at the source code, which wasn’t always very clear.

The prototypical example of this, in my experience,

was the

linear library,

which I reached for to get matrix math

without incurring a dependency on BLAS/LAPACK.

In part because there is no example code

and in part because the library is based

on the notoriously abstruse

lens library,

it took me several hours of scanning source code

to figure out how to create vectors and matrices

and how to access their entries.