Answer

Population codes are neural representations at the level of groups of cells. There are many examples of population codes, including sparse codes and holographic codes.

One famous population coding model is the "population vector" model from a 1986 paper by Georgopoulos, proposed to describe motor neuron tuning in primary motor cortex. In this model, each neuron in the population has a preferred movement direction, and the resulting movement is a weighted average of the preferred movements, where the average is weighted by firing rate.

Though popular at the time, it came in for some substantial criticism on theoretical grounds, which I review here.

Population Coding

Information about the outside world and plans for motor action are represented by the firing patterns of neurons – temporal sequences of action potentials, also known as spikes.

Usually, questions about the nature of this representation revolve around the behavior of single cells: Is information contained in firing rate or relative timing of spikes? How does a single synapse change its efficacy? What stimulus features predict firing changes in a cell?

We ask these questions because they are more tractable, that is, because we might hope to find answers to them. Unfortunately, they are essentially the wrong questions.

In general, the computational properties of groups of neurons should be an emergent property of the group, rather than merely a concatenation of the computational powers of individual neurons.

Population codes are answers to the more complicated questions that arise when multiple cells are considered at the same time: Should codes involve all cells or just a few? How can excitatory and inhibitory cells interact to produce computation? How can we store and retrieve memories using a population of neurons?

In the case of population vector coding, though, the computations of individual neurons are combined in a very simple way.

Population Vector Coding: Georgopoulos Model

We'll discuss population vector coding by means of a particular model, which was proposed in the 1980s to describe the behavior of neurons in the primary motor cortex of monkeys during a reaching task.

Our monkey has been trained to reach and press a button in return for a juice reward. There are eight buttons, arranged in a circle, and the monkey is informed as to which button to press by a blinking red light. In between each button press, the monkey returns its hand to the center.

We insert an extracellular electrode into the brain of this monkey and record from one or a few neurons at a time.

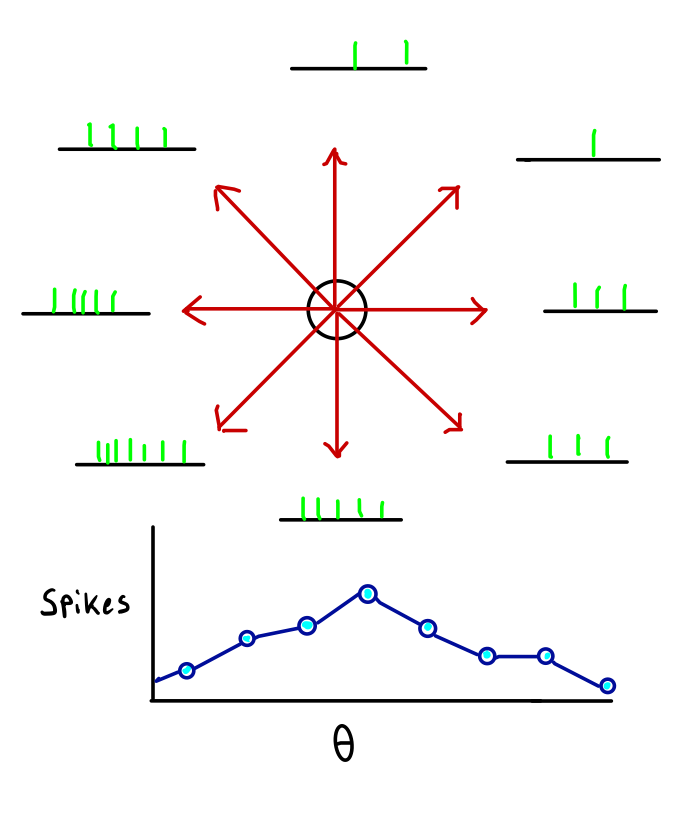

The results from recording a particularly nice neuron are shown below.

On top, we see a schema of the experiment, along with some data. The circle in the center represents the central region to which the monkey returns its hand on each trial. Each red arrow points towards the location of a button.

At the tip of each arrow appears a "spike train" – the black line is a time axis, and the green hash marks are action potentials. The spike trains at the tip of an arrow were recorded when the monkey was reaching towards the button indicated by that arrow.

The data represented by the spike trains has been aggregated into a "tuning curve" in the bottom half of the figure. Heights represent spike counts (population vector coding is a form of rate coding) and positions on the x-axis correspond to angles of motion \(\theta\)– that is, to button locations. This neuron has a "preferred direction" down and to the left.

Note, however, that the neuron fires a spike or two even when the motion is in precisely the opposite direction of it prefers. If we assume that the number of spikes fired on any trial varies by two or three spikes, then we have a serious problem: seeing five spikes from this neuron provides very little information about the intended motion direction.

But monkeys, like humans, are capable of very fine motions: a monkey would have no trouble touching a button separated by only a few degrees, but this neuron hardly discriminates between angles that are 90\(^{\circ}\) apart!

In population vector coding according to Georgopoulos, this apparent paradox is resolved through a population vector code. Each neuron's spikes are viewed as "votes" for motion in its preferred movement direction. When a movement command is generated, the resulting votes are combined and movement occurs in the average direction.

In mathematical terms, we take a weighted average of the preferred directions. Each direction is a vector, and so the resulting average is a population vector. To get even more mathematical, we can say that we are taking a linear combination in the basis set up by the neural tuning curves – by assumption, a radial basis – where the weights of the linear combination are determined by the firing rates.

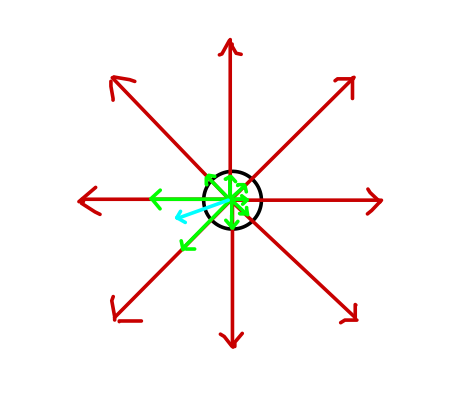

This results in a substantial increase in the possible accuracy of movement. In the image below, eight neurons with preferred directions pointing to each of the buttons (red arrows) are firing, with the preferred direction and spike count of each cell represented by the directions and magnitudes of the green arrows. The average, "population" vector that results (light blue) is in between two of the preferred directions. Small changes in firing rate can generate small changes in direction.

Problems with Population Vectors

During the 1980s, it was reported that population vector models could predict hand motion with a high degree of accuracy, and so it was believed that these models accounted well for the behavior of cortical primary motor neurons. That is to say, it was believed that cortical motor neurons represent preferred motion direction in Cartesian coordinates.

However, a close look at the mathematics of the population vector approach, as in, e.g., Sanger's 1994 Neural Computation paper precludes that conclusion.

Without diving into the mathematical details, the overall point is that if we assume that 1) neural firing is at least correlated with hand movement and 2) these directions of correlation are spread out in space then all of the reported results follow, without any need to assume that the neurons are actually engaging in population vector coding.

It's important to note that, though Assumption #1 sounds like an assumption that neurons are computing preferred directions, it isn't exactly the same. Importantly, the possibility is left open that there are more complex statistical dependencies than correlation between the neuron and hand motion, so long as the correlation is non-zero.

The broader point is that the results would be found whether the neurons were using Cartesian coordinates or not – so long as they produce a complete basis for 2-D or 3-D space, the analysis procedure used to create a population vector will produce statistically-significant results.

The broadest point is to be careful with models: usually, we are making a number of basic assumptions about the data that we have no reason to believe are true. We make these assumptions because they guarantee the correctness of our model – our linear regression or our correlation analysis. They provide these guarantees because they are powerful mathematical tools, and we should be careful that they are not too powerful to support our conclusions!

Before you think this kind of mistake is relegated to neuroscience past, consider this: recently, a number of papers have used compared the internal representations of artificial neural networks that perform difficult tasks, like object recognition, at a human level to the representations of cortical neurons. When they find correspondences, the papers speculate that this indicates some connection between the computations of artificial neurons and their biological counterparts: perhaps the brain does gradient descent, or has a convolutional architecture?

However, these are exactly the kinds of correspondences that could be, like the population vectors, simply artifacts of the definition of the problem – both of how we measure receptive fields and of how we train artificial nets.