Answer

The primary motor cortex is arranged somatopically – according to a map of the body. The amount of cortical real estate devoted to a given body part is correlated with the fineness of motion required of that body part.

Spiking in neurons in the primary motor area correlate with several basic movement properties: direction, speed, and strength.

Artificial stimulation of the primary motor cortex elicits simple movements, like twitches, flexions, and extensions.

Check out the UTH online neuroscience textbook for a bunch of neat visualiztions of this material!

The Organization of Motor Cortex

Like it's partner in crime, the somatosensory cortex, motor cortex is organized according to a topographic map of the body.

Topographic maps are unlike the maps we use to navigate. On those maps, the key property to preserve is distance – as we move one mile in the world, we should move one foot on a navigational map with a 5,280:1 scale.

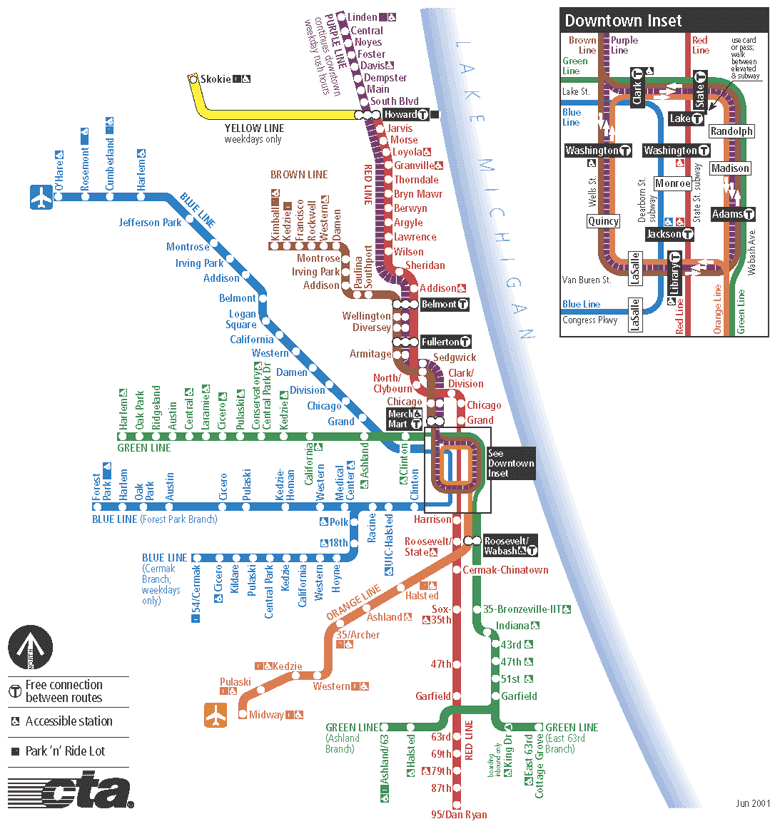

Topographic maps are more like the maps of subway systems. Below is a map of the subway system of my home city, Chicago. On this map, moving an inch will sometimes move you just a dozen yards, and sometimes it will move you hundreds of feet.

The key property preserved by this map is neighborhood, rather than distance. We can see which stations are connected to which, and how many stops are between them.

The map of your body in the motor cortex is like that: at some points, moving a millimeter in motor cortex will move you just from one part of your hand to another. At others, moving a millimeter will take you from a region that controls a muscle in your abdomen to a region that controls a muscle in your neck.

Nearby neurons, however, will almost always control nearby parts of the body, where nearby is on the scale of a few microns. Mathematically, we would say that there is a smooth map from the surface of your body to the surface of the motor cortex. In neuroscience, we call such a map a somatotopic map.

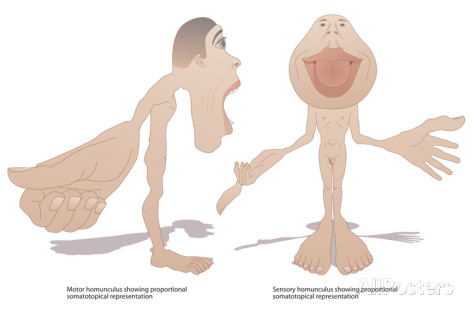

What determines how large the area of cortex that corresponds to a particular body part is? Certain body parts need to be very carefully controlled: for humans, these include the fingers and the lips, while for a mouse, these might be the whisking mucles. Other body parts need only very gross or simple control: the trunk, for example, or the legs.

The finer we need to control a body part, the more cortical area is devoted to that part. A related principle controls how much cortical area is devoted to sensory stimuli. The result is that there is also a somatotopic map in the somatosensory, or body-sensing, part of the brain.

One cool visualization of this kind of map is called "the homunculus", which is Latin for "the little man". The homunculus for a somatopic map is drawn with his body parts sized proportionally to the amount of the map used by the body part. Representations of the motor and somatosensory homunculi appear below.

It is important to note that, contrary to what you might expect, the motor cortex is not organized according to the specific muscle controlled by a given neuron. Within the region corresponding to the arm, for example, we don't find sub-regions corresponding to the tricep, bicep, etc.

Instead, we find these neurons mixed in with one another, presumably because most of our movements require the coordination of many muscles within a body part, rather than the motion of a single muscle.

An Aside on Coding

Before describing the following results, I'd like to note that we don't know what any part of the cortex really "represents" at the level of a single neuron's action potentials. One reason for this is that we stil don't know how neurons encode information. Are codes based on relative spike timing, or on total spike count in some time window? Is that even a sensible question? Are stimuli encoded at the level of a single cell or small group of cells, or is information aggregated from an entire population of cells? One famous model of M1 function uses a population-based rate code, but it has come in for some serious criticism. On the other hand, designs for neural prosthetics based on that model have been moderately successful, even if they won't be performing rocket surgery.

We'll ignore most of that complexity below, but I wanted to put it out there so that I don't mislead any of my readers into thinking we understand the brain!

Coding in Motor Cortex

Several basic movement features are represented by the patterns of action potentials in neurons of the primary motor cortex: strength, speed, extent, and direction.

Strength-, speed-, and extent-representing cells increase their firing rate when those parameters of the movement are increased: more spikes per second means stronger, faster, or further movement of the given muscle.

You might wonder how you distinguish between strength-representing and speed-representing cell. This is best seen with targeted movements, or movements to a specific location, as when I move my coffee cup to my lips using my arm and hand. In these movements, speed starts at 0, then increases to some peak, and then decreases, ensuring that I don't smack my face with my mug. Note that the force is going to proporitonal to the derivative, or rate of change, of the speed, thanks to Newton's Laws.

Some neurons fire at a rate proportional to this derivative, the acceleration, and so are force- or strength-representing cells. Other neurons fire at a rate proportional to the speed directly, and so are speed-representing cells.

The encoding of movement direction is a separate case, and is covered more thoroughly in a separate blog post. In short, according to a popular model, each neuron has a preferred movement direction, and during a motion, neurons with many different preffered directions fire. The resulting movement is in the direction that is the weighted average of the directions preferred by the firing neurons, with the weights determined by the number of spikes.

More complicated movement features, like the components of a motor sequence or the goal state of a movement, are represented by other cortical areas.