Answer

What is the problem of invariance?

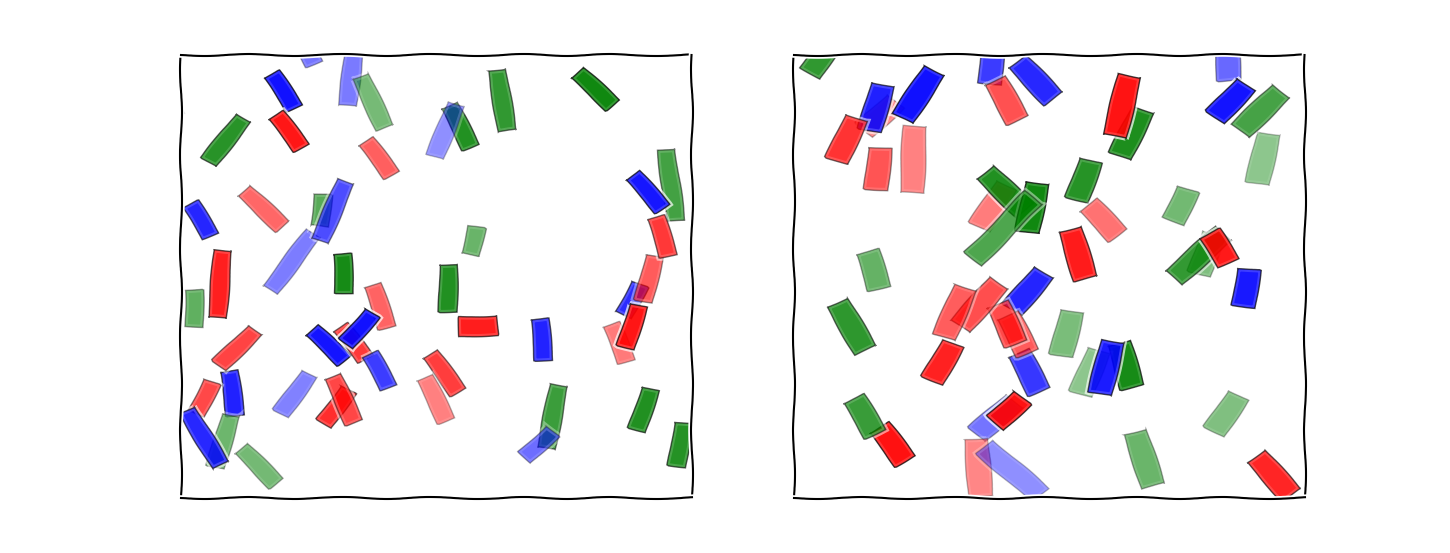

Fixate your gaze in between the two panels below. Which of the panels contains a horizontal bar?

If you answered "the one on the left", you are correct, and your brain successfully solved the "problem of invariance".

Each bar had five basic properties: size, location, transparency, color, and angle. Four of these were irrelevant. Because of this, the neuron or population of neurons that represented your answer to this problem had to be invariant to those four properties.

That is to say, if I had varied the colors, sizes, locations, and transparencies of every bar in the left image without changing the angles, the response of the neuron or neurons that you used to identify the presence or absence of the horizontal bar should not have changed.

This is a relatively trivial-seeming problem, but in its most general case, the problem of creating invariant representations of signals is extremely difficult. For the mathematically inclined: it is closely related to the problem of arbitrary non-linear manifold learning.

How can the problem of invariance be solved?

This general case includes specific problems like:

- How do I recognize the same word spoken in different voices?

- How do I maintain a stable percept of an object as it rotates?

for which we have reasonable solutions: for the first, Google mixed up a cocktail of powerful non-linear probabilistic models to operate voice search ("OK, Google"); for the second, Facebook created DeepFace, to recognize billions of human faces across a range of angles.

However, quite apart from the dubious biological plausibility of these so-called "neural network" approaches, their need for massive quantities of pre-labeled data make them unlikely candidates for the algorithm that humans and animals use to, e.g., recognize predators.

What are some models for how it is solved in the brain?

The simplest model for an invariant neural circuit is built on the Hubel and Wiesel model of simple cells in primary visual cortex, and solves a problem quite similar to our first example.

We make the problem easier by restricting the bars to be black and white and making them all the same size and transparency. Our goal, then, is to make a circuit that detects a certain certain size horizontal bar no matter where it appears in the image – a "spatially-invariant" circuit.

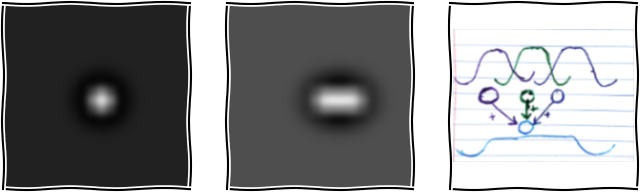

We begin with a cell that can detect a horizontal bar at given location, the so-called "simple cell". Simple cells perform an AND-like operation on the responses of retinal ganglion cells, allowing them to detect a bar of light surrounded by darkness (or vice-versa).

Fig. 1 Simple cells concatenate retinal ganglion cell (RGC) responses. The left panel shows the "receptive field" of an ON-center RGC. It can be thought of as the stimulus that maximally excites the neuron. The center panel shows the result of adding together three ON-center RGCs with slightly shifted centers. The right panel is a schematic of the necessary neural circuit, simplified to the one-dimensional case. Three neurons, purple, green, and dark blue, have ON-center receptive fields, each with a slightly different center, shown above. They provide excitatory input (arrows) to the sky blue simple cell. Try drawing this cicruit yourself in two dimensions! Check out another post for more details on the biology and mathematics underlying this circuit.

This single simple cell can't solve the task presented at the beginning of this post. It responds to a horizontal bar only if it is located at its particular receptive field.

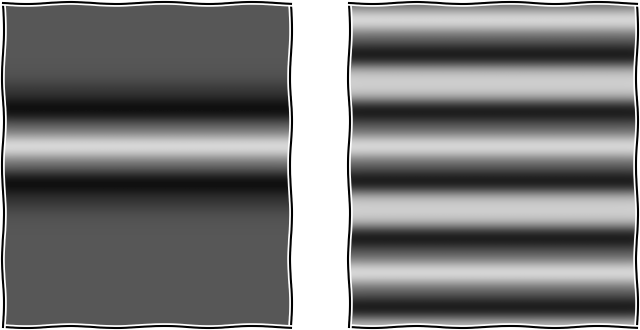

We can make progress by taking inspiration from the way we built this horizontal bar receptive field: we combined simpler elements additively. If we take multiple neighboring simple cells with a horizontal orientation, we can make a straight line covering one height in sensory space (see left panel below).

Then, if we combine several of these "multibar" detectors, each at a different and well-separated y-coordinate, we can get a cell that detects a horizontally-oriented bar at any x coordinate and with its center at one of those y-coordinates. The receptive field of such a combination is shown in the right panel of Figure 2.

Fig. 2 Combining simple cell RFs gets us closer to our goal.

The problem with this approach is obvious: this cell is now more a detector of this horizontal stripe pattern, rather than being a specific, invariant detector of horizontal bars. Worse still, there are "blind spots" in between our stripes. What would happen if we tried to filled in those spots with more cells like the one in the left panel?

We can make a drastic improvement by including lateral inhibition, which introduces competition between our cells. This works like so: every simple cell activates an inhibitory cell, which makes connections to all the other simple cells in our circuit. When a simple cell becomes active, it engages this inhibitory cell, decreasing the activity of all of our other horizontal bar detectors. With careful tuning, we can make sure that this circuit settles into a state where either only one cell is active, or no cells are active. This circuit is known as the "Winner-Take-All" circuit, for obvious reasons.

Generalizability

In some sense, the model described above is super general: Assemble your feature detectors into an array that "tiles" or "fills out" the variable that you want to be invariant to, then implement competition to ensure only one can be active. Artificial neural network aficionados will recognize this as a form of convolution plus max-pooling, which has proven highly successful at producing useful, invariant representations of complex signals.

However, there are some pretty big caveats that come with our proposed model. it's certainly inefficient: each invariant detector is composed of many variant detectors. This is especially bad in two cases. First, the complexity compounds if we try and create a hierarchy, i.e. if we have an invariant detector composed of other invariant detectors. Second, the complexity increases exponentially as we add additional invariant dimensions: if we wanted to be invariant to orientation, as well, we'd need a circuit like the one described above for each orientation, plus competition between a set of output neurons representing each circuit.

Furthermore, we sidestepped the problem of relating our transformations. It was easy to see what a spatial translation of a bar was, and the result of this translation was still substantially similar to the original. When the transformation is something like "a phrase said with an American accent" to "the same phrase said with an Indian accent", the relationship in stimulus space is not so clear.

Lastly, this circuit has no capacity for learning and discovery: invariance is a property that we painstakingly built into it, rather than the goal of a learning process or an emergent property. This is closely related to our problem of relating transformations, since one way of establishing these relationships is learning them.

Hopefully that makes it clear why solving the "Problem of Invariance" is so hard – it means nothing less than "recognizing the structure preserved by transformations", where that structure and those transformations can have arbitrary form!