Answer

Extracellular electrodes detect changes in electrical potentials from a distance. As such, the signals they see are much smaller, making it impossible to see non-spiking activity.

The performance of extracellular recording techniques is limited by interfering noise, which can be quite complex (non-stationary, non-Gaussian, signal-correlated). This is particularly acute when trying to record multiple neurons using a single electrode, leading to the (still-unsolved) spike-sorting problem.

The Old, Gold Standard: Intracellular Recordings

Neurons represent information using a fluctuating electrical potential across their cell membranes – the membrane potential. To a first approximation, measuring the behavior of neurons means measuring this electrical activity.

The good news is that this means neural activity can in theory be measured at a distance, using electrical equipment, just like we can see and hear from a distance. Compare this to the senses of touch or taste, which require direct physical contact – note that we've made much more progress with television than with smellevision!

The bad news is that, in practice, these electrical signals rapidly decay below the point where we can detect them: they fall off with the square of the distance, just like gravity. That means that a signal that is just small enough for a neuron to reliably use it to represent, store, or transmit information in the face of the unreliability of squishy biological materials is going to be hopelessly small when measured from a distance.

Because of this, the "gold standard" for observing neurons involves getting up close and personal. We need to get our electric field detector, or "electrode", right up against or even inside the neuron.

This method of measuremant has all of the disadvantages that observing systems with touch or taste would: it perturbs the system and makes it hard to observe more than one thing at once (just try observing your friends and family with taste instead of hearing and sight).

Extracellular Recordings to the Rescue

Luckily for us, neurons only use tiny signals for ther internal processes, like dendritic propagation. When neurons want to talk to each other, they use much larger signals: action potentials. Since our brains are composed of many interacting neurons, a solid case can be made that the most important information must be represented in these communiques between neurons.

Because action potentials are so much bigger than the internal processes of the neuron, the so-called "subthreshold activity", we can observe them from further away. Instead of having to get up to or inside the neuron, we can sit close by, maybe 100 microns away, (about the width of a pixel in your monitor).

This has several advantages:

-

The finicky and delicate process of attaching our electrode to a neuron is completely avoided.

-

With no need to attach our electrodes, we can stick them in as a group however we like. If we want to record from a column of neurons, we stick them in depthwise; If we want to record from a broad area, we stick them in as a grid.

-

Though a particle of dust is small, it's a good bit larger than a neuron's cell body, which is about 10 microns wide – or about the size of dust mite excrement, just one of the many fascinating components of our aforementioned particle of dust. This means we can observe several neurons at the same time!

Drawbacks to Extracellular Recordings

The picture for extraceullular recordings is not entirely rosy. The ability to measure more than one neuron at once is both a blessing and a curse. We've gone from leaning in close enough to hear a neuron's whispers to standing a few feet away, and we're in a crowded bar.

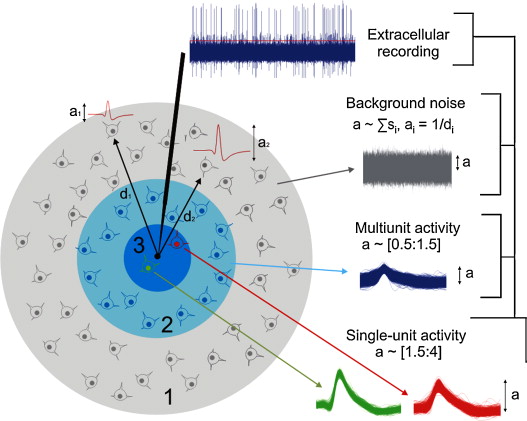

The image below, from this paper from Quian Quiroga's group, gives a sense for just how much interference there is.

Our detector is in black, with its tip right in the center. The innermost circle is the mote of dust in which we can reliably detect action potentials.

The gray, outermost donut contains cells that are far enough away and numerous enough that the central limit theorem holds. In simple terms, this means that they just sound like static – "white noise". Static is easy to tune out.

The light-blue donut contains cells that aren't close enough to hear well but aren't far enough to tune out. They are like the loud guy at the bar two tables away whose conversation keeps bleeding into yours. Just as in the crowded bar case, these cells are the hardest to filter out, though the full paper goes a long way towards solving this problem with modeling.

A quick aside: if you're familiar with statistical inference techniques, you might object that this is a version of the "cocktail party problem", which has been well-solved by, e.g. Independent Component Analysis. Unfortunately, our problem is a bit tougher than the cocktail party problem. The conversations in the metaphorical cocktail party are assumed to be independent. Nearby neurons, however, are correlated with one another (think, e.g., of columnar structure), and so approaches to solving the cocktail party problem tend to be over-eager to lump together correlated but distinct neurons.

Our final problem comes in the central circle, the dust mote wthin which we can reliably detect activity. As you can see, there are two neurons, red and green (apologies to the color-blind; I didn't make this figure!), both of which generate reliable signals, or waveforms, in our electrode.

We now have a souped up version of the same problem we encountered in the light-blue donut. When we detect an action potential, we have to assign it to one of the two neurons, using only the slight differences in shape (e.g. the green waveform is skinnier and taller, usually, than the red one). Worse still, we don't usually know how many neurons we are listening to, making the problem of assignment much more difficult.

This process, known as "spike-sorting" in the electrophysiology community, is just one example of a particularly thorny problem in machine learning: blind (non-parametric) clustering or unsupervised category learning. Since discovering structure in information is a) one of the principal functions of intelligence and b) technically impossible in the general case it is unsurprising that there is no one-size-fits-all approach.

Interested parties are referred to this 1998 review by Mike Lewicki. Despite its age, its clarity and breadth give it staying power. A more modern take appears in this Scholarpedia article by Quian Quiroga (of "Jennifer Aniston cell" fame).