Before I begin my answer in earnest, let me note that the following material is some of the most conceptually difficult material in your standard introductory neuroscience course, especially for students with a minimal chemistry/physics background.

If you're having trouble with this material, the best recommendation I can give you is to go to multiple sources and see the material from a variety of angles and multiple times, until it starts to become intuitive.

Check out the references for some useful links to other explanations of this material!

Answer

The ionic basis of the membrane potential is a conflict between two fundamental physical processes: the diffusive and electrical "forces" acting on ions. Like all particles, ions prefer to be spread out, rather than clumped together – they prefer a state with higher entropy, or disorder. However, if charges are balanced in a system, and then the ions of a particular charge spread out, leaving behind the ions of the other charge, they create a charge imbalance – an electrical potential.

This is precisely what occurs in the cell, where negatively charged molecules, like DNA and other organic anions, are prevented from diffusing across the membrane, but there are special channels that allow monoatomic ions, like Na+ through. The resulting charge difference establishes an electrical potential – and so an electric force that tries to equalize charge inside and outside the cell.

The result of putting the electrical force and diffusive force in conflict with one another is an equilibrium – a point at which the flows caused by each force are equal and opposite. In general, individual ions have a greater effect on charge and potential than they do on concentration, so we call this equilibrium state of the system the "equilibrium potential" or the "resting potential", rather than the "equilibrium concentration".

Single-Ion Case: The Nernst Equation

We can quantify the value of the electrical potential at this point by following up that intuitive explanation with some good old-fashioned physics. For a single ionic species $X$, the process is straightforward enough that I have reproduced a sketch derivation at the bottom of this post, for the mathy types. The resulting equation is called the "Nernst Equation", after its discoverer, Walther Nernst:

Let's talk about the first term. Two of its components are just constants that relate our units. R is the ideal gas constant, which relates our units of energy to our units of temperature. F is the Faraday constant, equal to the charge, in coulombs, per mole of electron – it relates our units of charge to our units of concentration. T is just the temperature. If we assume we're talking about a warm-blooded creature, and choose to measure electrical potentials with milliVolts, we can simplify these three terms into one number – about 25:

That's not as spooky! It gets better, too: z is the charge of the ion, which is only one of three numbers in a biological context: +1, -1, or +2

So the primary determining factor for the equilibrium potential for an ion is the ratio of the ion's concentrations outside and inside the cell. The logarithm is equal to 0 when its argument is 1. In that case, the resting potential is 0: if the concentrations on the inside and outside are equal, then there is no diffusive force, and so nothing for an electric potential to balance. If the ion is positive, then the sign of the resting potential difference is the same as the sign of the logarithm of the ratio of its outside and inside concentrations. Having more ions outside the cell than in will give a ratio greater than 1, and therefore a positive value of the logarithm. Therefore, flows will be balanced when the cell is positive relative to extracellular environment. This positive charge creates an electric field that repels the positively-charged ions that would otherwise flow down their concentration gradient and into the cell. For a negatively charged ion, the negative sign from $z$ flips the sign of the equilibrium potential, and we get exactly the same story, mutatis mutandis.

Multiple Ions: Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz Equation

In the preceding discussion, we only considered cells with membranes permeable to one ionic species. Things get a bit more complicated for multiple ions, since their electric fields all add onto each other while their diffusive tendencies are totally independent. Therefore, we're no longer looking for the voltage at which any individual ion has a net flow of 0 – instead, we're looking for the voltage at which the net flow of all ions is 0. At this potential there is no net flow of charge, and so the membrane potential won't change over time.

As you might guess, we can take into account multiple diffusive flows by adding them up – two outward flows need to be cancelled by an inward flow of twice the size. However, not all flows are created equal. Biological membreanes are selectively permeable – instead of having simple physical holes for ions to flow through, membranes have selective proteins called [ion channels]http://charlesfrye.github.io{site.baseurl}}/18) that only let ions of a particular species through.

If there is a very large concentration difference, but no or very few holes in the membrane for the ion to flow through, then very few ions will flow – imagine a water balloon with a pinprick hole at the bottom compared to one with a chunk taken out. Therefore we need to take the relative permeabilities of the ions into account.

The resulting equation assuming all ions have a charge of 1 or -1, which works well for most neuroscience contexts, is the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz Equation:

\[\begin{align*} \Delta V &= 25*\ln\left(\frac{\sum_{+}{p_x[X]_o}+\sum_{-}{p_x[X]_i}}{\sum_{+}{p_x[X]_i}+ \sum_{-}{p_x[X]_o}}\right) \end{align*}\]Here p stands for permeability. Note that we're doing two separate sums, one for positive ions and one for negative ions. Note further that the arguments are different for these two sums: the ratio for negative ions is "upside down" relative to the ratio for positive ions. That is, on the top of the ratio, we're summing up positive ion concentrations outside the cell, but negative ion concentrations outside the cell, whereas the situation is reversed on the bottom.

The algebraic reason for this situation is fairly straightforward: the z on the outside of the log for negative ions is negative one. When we want to combine multiple equations with different values for z, we need to bring the z inside the logarithm. Negative one times the log of x is equal to the log of x-1, and so we need to flip our ratio.

But we're talking about biology here, not pure math, so there'd better be an explanation in terms of the actual system. And there is!

Remember that we're trying to balance flows of ions with an electrical field. An electrical field that pushes against the flow of positive ions in one direction will add to the flow of negative ions in the same direction – a repulsive electrical force for positive ions is an attractive force for negative ions. Because of that, we need an equal but opposite electric potential to counteract a concentration gradient of negative ions instead of positive ions. Flipping the ratio inside the log gives us negative one times the original result – equal but opposite.

Note that the GHK equation gets you a voltage at which net flow is 0, but individual ion flows can be non-zero. This means that ions will be flowing into or out of the cell, abolishing the very concentration gradients that set up the voltage difference in the first place! Because of this, cells have to expend energy to keep up their concentration gradients. The primary protein in this system is the sodium-potassium exchanger, which cleaves ATP in order to push sodium and potassium against their gradients.

These constant flows are the reason why the ion channels underlying the resting membrane potential are often called "leak" channels.

An Electrical View: The Equivalent Circuit

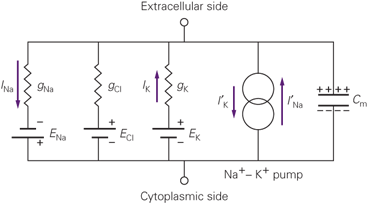

The foregoing discussion has taken a primarily chemical view of the membrane potential: we have a permeable membrane, concentration gradients, etc. There is a parallel and equivalent view of the membrane potential that is primarily electrical: the Equivalent Circuit.

In this view, the concentration gradients are batteries – they produce an electric potential – the semi-permeable membrane is a resistor – it allows variable amounts of current through, depending on the permeability – and the intra- and extra-cellular fluids are wires – they pass current without resistance.

We can combine all these pieces together to get a picture of the equivalent circuit:

Fig. 1 Equivalent Circuit for a neuron. From Kandel, 5e.

We've already talked about the first four of these elements, moving from left to right. There are three concentration gradients and their associated permeabilities, here referred to by the letter g, which stands for conductance for no good reason. Conductance is the inverse of resistance. Each conductance gX passes a current I of ion X, powered by the concentration gradient EX. These are the flows we've been talking about all along. The fourth element is the sodium-potassium exchanger.

We can already benefit from this new framework. The application of a few simple circuit laws gives us a new, easier to use substitute for the GHK Equation:

\[\begin{align*} \Delta V = \frac{\sum g_X E_X}{\sum g_X} \end{align*}\]Where the values EX are just the values we got from the Nernst Equation. This is a very elegant way to express the membrane potential: it is a weighted average of Nernst potentials, where the weights are the sizes of the ionic conductances. This interpretation will come in handy when we want to think about the action potential.

The fifth element of the equivalent circuit has so far been outside the scope of our discussion.

We've been considering equilibirum potentials, or steady states of the membrane potential system.

Some of the most interesting properties of neuronal behavior, however, involve transient responses.

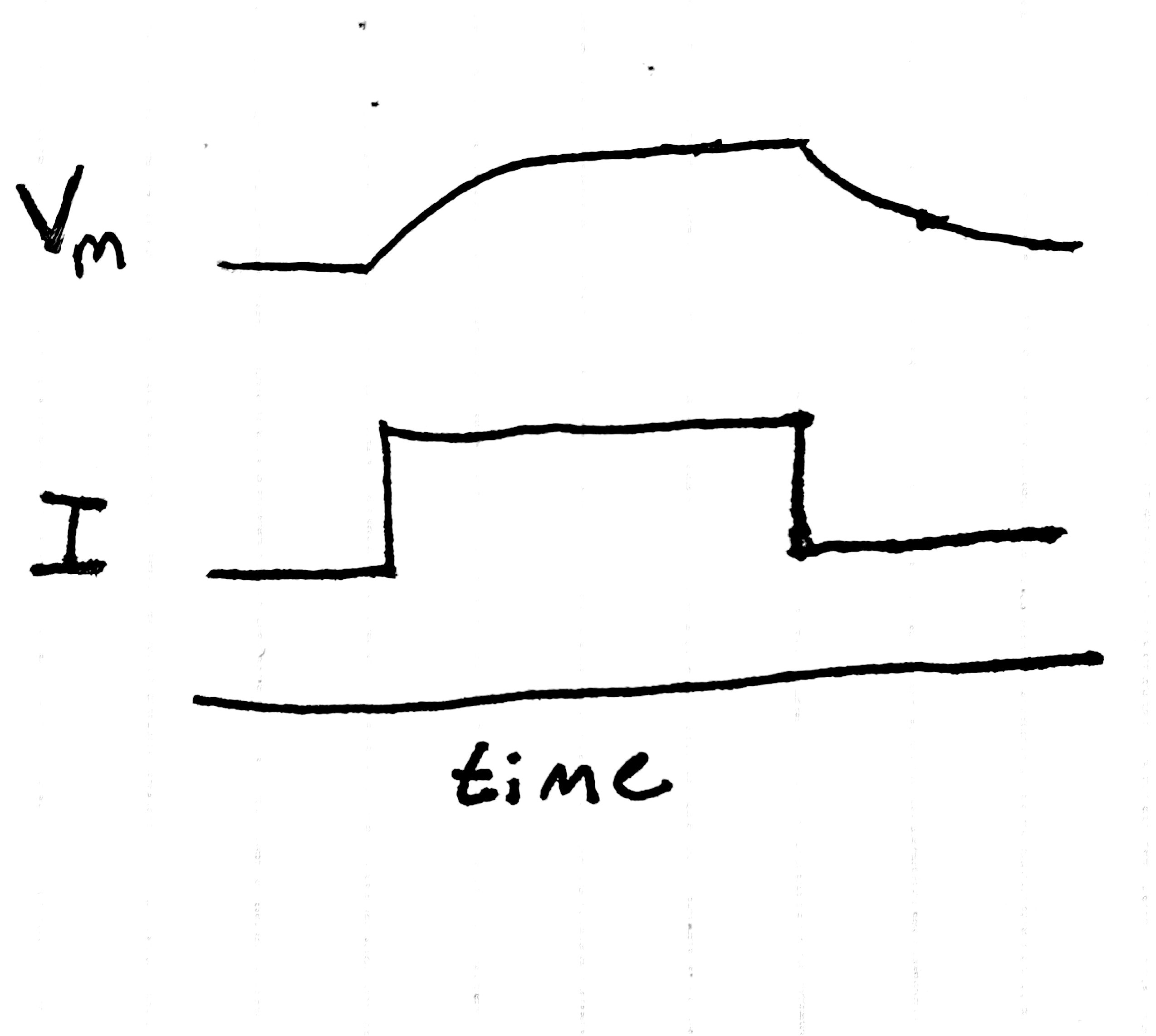

Consider the results of the following experiment:

we inject a step of current into a neuron, then record the membrane potential as it changes over time.

If our picture of the neuron up to this point were totally correct,

we'd expect just to see a step in the membrane potential –

the voltage would change to a new value instantly,

and ionic flows would change to reflect this fact.

Instead we see the following:

Fig. 2 The result of a step current is not a step change in voltage.

Instead of immediately reaching the expected voltage, the neuron takes its sweet time getting there. What gives?

The answer lies in the fifth element in the equivalent circuit above: it is a capacitor. In circuit design, capacitors are made by separating two metal plates with a resistive medium. The more close contact the plates have, the more that charge build-up on one plate can cause build-up of the opposite charge on the opposite plate. We can quantify this with a number, the capacitance, which has units of Farads. In the neuron, our "plates" are the intra-cellular and extra-cellular fluids right up against the membrane, and our "resistive medium" is the phospholipid bilayer that forms the bulk of the membrane.

So when we inject current into the cell, the first place it goes is onto these capacitor plates. This doesn't change the potential across the membrane, so at the very beginning of our current injection, the membrane potential is unchanging. What it does do is make it harder for later current to add onto the capacitor: the capacitor "gets crowded", and so later charges are more likely to take an alternate route. The only alternate route available is through the conductances, so as time goes on, less charge goes onto the capacitor and more goes through the conductances.

My favorite loose metaphor for this process involves a bunch of human couples, separated by a river with just one rickety, dangerous bridge. For the sake of matching the underlying science, let's be heteronormative for a bit and say the couples are all male-female. If we drop all of the boyfriends off on one side of the river, the first thing they're going to want to do is meet up with their girlfriend. However, the rickety bridge is just too scary, so they instead walk up to the shore, call out for bae, and successfully meet up without having to risk their lives.

Fig. 3 A visual aid.

But after enough of the boyfriends adopt this strategy, the riverfront will start to get crowded. It will be crowded enough, in fact, that a few intrepid souls will start crossing the bridge, frustrated by their inability to reach the shore. This will, of course, change the gender balance, unlike the folks shouting across the river.

In the neuron, positive and negative charges are the two genders. The membrane is the river, which has tragically separated our loving couples. The conductance represents the quality of the bridge: a higher conductance means a safer, less spooky bridge. The capacitance stands in for how easy it is to talk across the river: if the river is thin and meandering, many more couples can comfortably line up to chat. If, on the other hand, the river is very wide and straight, the banks will fill up quickly and the motivation to cross the bridge will increase more quickly as well.

As you might have guessed from all the discussion of time in the preceding paragraphs, the equivalent circuit model lets us use the properties of conductance and capacitance to predict the unusual time course we saw in Figure 2. The details of how we can do so are a bit outside the scope of this post, but if you're curious, check out the Wikipedia page on RC Circuits. If you've ever worked with electronic or electric instruments, some of the ideas will be very familiar!

A Brief Derivation of the Nernst Equation

WARNING: MATH

In the above, ∇ means "gradient", or multi-dimensional derivative. On the right we take this gradient, or difference, with respect to the concentration of ions, c. We know that the spatial flow of ions due to diffusive forces will be inversely proportional to this gradient, since ions flow down their concentration gradient towards areas of low concentration. Because we will be choosing our units arbitrarily, we don't know what that proportionality constant will be, so we just call it kd. Note that concentration is a function of spatial position, which we denote by x.

On the left, we do something similar, but with respect to the electrical potential function, Φ. We want to know the flow, or flux of charges, so we need to take into account their concentration, c. ke, like kd, is a constant that relates electrical flux to our system of units. So the left side of Eqn. 1 just says that the electrical part of our current is proportional to our potential difference and to the concentration of charges acted on by that difference. The right side says that our diffusive current is proportional to the concentration gradient, with some constant kd that relates the flow to our system of units. We want these things to be equal and opposite.

We make some boilerplate simplifying assumptions: that we're talking about 1-D flow normal to an approximately planar membrane in a point-like spherical cow, etc. After re-arranging, we integrate both sides between the inside of the cell i, and the outside, o, and get Eqn. 2. All of a sudden, the Nernst equation is in sight, and it's just a matter of cranking through to Eqn. 4.

Nernst related the two proportionality constants, discovering the terms they had in common and giving rise to the more familiar form of the "Nernst Equation" that appears above. However, the best and most general proof of the relation is actually due to Einstein!

Refs

- Kandel & Schwartz 5e, Membrane Potential and the Passive Electrical Properties of the Neuron, Ch. 2-6.

- Khan Academy is an excellent resource for this material. The basics are in their material on the heart, especially the lectures between "Membrane Potentials I" and "Permeability and Membrane Potentials", while more neuron-specific information is in their material on the nervous system, in particular the lectures from "Sodium-Potassium Pump" to "Electrotonic and Action Potential".