Answer

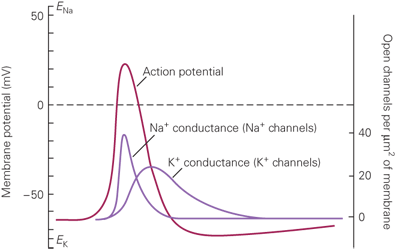

First, let's review the basic features of the action potential, as discovered and described by Hodgkin and Huxley. The following figure will be helpful throughout.

Fig. 1 Prototypical Action Potential. From Kandel, 5e.

In magenta, we see the "action potential". It begins with a sharp upward swing of the membrane potential. This rapid increase occurs when the membrane potential reaches a critical value, called the threshold potential.

The membrane potential reaches some peak value, generally somewhere above 0, sometimes as high as +35 or +55 mV†.

Then, just as rapidly as it increased, the membrane potential decreases again, falling down below the resting potential* for a brief period before returning to normal.

The primary proteins underlying these phenomena are voltage-gated ion channels, which are tiny pores in the membrane that open in response to changes in voltage. Two players, the fast-inactivating sodium channels and the slow potassium channels, act in concert to produce a positive feedback loop first, driving the membrane potential up, then a negative feedback loop after, pushing the membrane potential down. The counts of active channels of each type are shown as purple lines in Figure 1.

The fast-inactivating voltage-gated sodium channel is responsible for the positive feedback loop. These channels are more likely to open when the cell is depolarized, and their effect is to depolarize the cell by allowing sodium to flow down its electrochemical potential^, i.e. into the cell. This depolarization will, naturally, cause more of these channels to open, and so on and so forth for the first 1 ms or so.

Two mechanisms combine to shut this train down.

First, the sodium channels are inactivating. This means that, regardless of the membrane potential, they can only remain open for a short period of time before they close themselves automatically. After closing in this manner, they are briefly unable to re-open. If you'd like to know more, check out this post reviewing inactivation mechanisms.

Second, the potassium channels are slow activating. Their voltage dependence is roughly similar to that of the sodium channels, but they take longer to open. They allow potassium to flow down its electrochemical potential, i.e. out of the cell. This efflux of positive charge causes the neuron to hyperpolarize.

The combination of these two effects is a dramatic reversal of the membrane potential, down close to the equilibrium potential for potassium. As the slow potassium channels slowly close in response to this hyperpolarization, the membrane potential slowly returns to its original value – something like -70 mV for a cortical neuron.

Refs

- Kandel & Schwartz 5e, Propagated Signaling: The Action Potential, Ch. 2-7.

- Khan Academy is an excellent resource for this material. Check out their lectures on the nervous system, in particular on "Electrotonic and Action Potential".

Footnotes

† But never above the equilibrium potential for sodium. Why? HINT: Consider the Circuit Equation. What determines the maximum value for the membrane potential?

* But never below the equilibrium potential for potassium. Why?

^ If you need a review on the electrochemical potentials of the neuron, check out this post.