Answer

Ion channels are proteins that create selective pores in the otherwise mostly impenetrable cell membrane. These proteins are critical to neural function, since they underlie the membrane potential and the action potential

Ion channel proteins create pores by organizing into a tube-like structure, where multiple alpha helices stick together in a ring. The interior of this tube is an aqueous pore through which ions can flow, while the exterior is relatively hydrophobic, so that it can sit comfortably in the membrane.

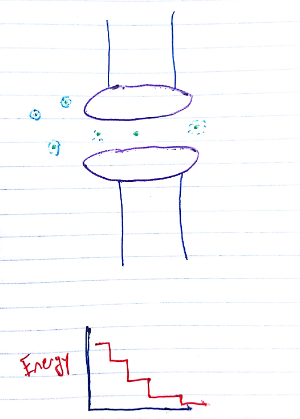

The pores allow ion flow by setting up an "energy staircase" of sorts (see Figure 1). There are few relatively discrete states that are energy minima, with each lower than the last. The final and lowest energy state has the ion on the other side of the cell membrane. When multiple ions are present, they push one another down this staircase. Energetically, the process is akin to the electron transport chain in oxidative phosphorylation.

Fig. 1 Energetic view of ion flow through a channel. We're looking down on the channel (purple), perpendicular to the direction of motion. Ions are green, with the hydration shells in light blue.

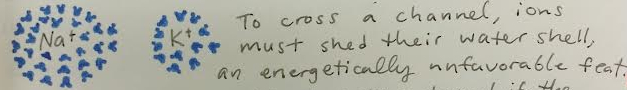

You'll notice that the ions have a tiny, light-blue cloud around them in the drawing above. This represents the hydration shell, a set of "hanger-on" water molecules that attach to ions in solution. Figure 2 shows these hydration shells up close. The drawing is courtesy of Christine Liu, neuroscience graduate student and visual artist.

Fig. 2 Hydration shells up close.

Hydration shells are critical for the function of selective ion pores. To understand why, let's take a step back and consider just how difficult the job of a selective ion channel is. If the channel is distinguishing, as in the question, between K+ and Na+, it doesn't have much to go on. Making the channel smaller works to keep out riff-raff like proteins and even small molecules, but it can't work to keep out Na+. In fact, K+ is slightly larger than Na+: it has an extra energy level of electrons, so its valence shell is bigger. To make matters worse, the ions have the same charge, +1.

The solution to this problem is to take advantage of the hydration shells. These shells are made up of many water molecules, arranged in a very predictable structure to neutralize the charge of the ion. For all cations, the water molecules will be pointing their electron-rich oxygen atoms in, but further details depend on the size and charge density of the ion in question.

Ion channels seize on these details to create a filter that selects for specific cations. If you looked very closely at the diagram above, you might've noticed that as the ion passes through the pore, the light blue hydration shell disappears, only to reappear when the ion exits on the other side. This is exactly what happens in the actual system. The pore is too small to fit the ion AND its hydration shell, so the H2O has got to go.

The loss of a water molecule is normally energetically disfavorable: the formation of hydration shells is spontaneous and so energetically favorable. So, the walls of the pore are cleverly constructed to make this transition favorable. In this particular case, negatively charged residues are positioned just right so that they can take the place of water molecules in the hydration shell at each step. To get selectivity, a given protein just has to "mimic" the hydration shell of one ion in particular, while doing a poor job mimicking that for a similar ion.

There are more (exciting!) details on this front, thanks to X-ray crystallography and molecular dynamic modeling, but this is the general picture.

Refs

- Kandel and Schwartz, 5e. Ion Channels, Chapter 2-5.