Answer

"Homeostatic plasticity" refers to a collection of processes that allow neurons to adjust how sensitive they are to their inputs. As with any homeostatic process, this form of plasticity ensures that neural activities (e.g. firing rates) neither grow without bound nor do they shrink to nothing.

Homeostasis Means Balance

"Homeostatic" is a fancy way of saying "keeping things in balance". We sweat when we're hot to cool ourselves down: sweating is a homeostatic process. Other examples include:

- Thermostats and air conditioning

- Choosing to take the bus only when there's traffic

- Supply and demand in economics

I'm sure you can think of more!

Gains and Guitars

The key purpose of homeostatic plasticity is the modulation of neural gain.

If you've ever noodled around with an electric guitar, you may've noticed a knob on the amplifier called the "gain". This knob acted sort of like the volume knob on a car stereo: increasing gain made the guitar louder, while decreasing the gain made the guitar quieter.

If you're like me, you turned that sucker up to 11. If you did, you might've noticed that the guitar started sounding less "clean". Instead of mellifluous notes à la Carlos Santana, you got discordant crackles, Joy Division style.

In addition to being hella radical, this is an excellent demonstration of how gain affects an input signal. When we pluck the strings of the guitar, they wobble complexly, which the tiny magnets in the guitar detect. They send these little wobbles into the amplifier, which turns them into big wobbles: the vibrations of the air that our ears detect.

Changing the size of wobbles (in more scientific terms: "signals") is exactly the meaning of gain. A gain greater than 1 means the wobbles get bigger, while a gain of less than 1 means the wobbles get smaller. To put a finer point on it: applying gain to a signal means scaling it, multiplying it by some factor we call the gain.

Gains and Distortion

When we turned the gain on our electric guitar down too low, we didn't hear a copy of our signal anymore. We just got silence. If our gain is small, but not exactly zero, this is because our ears aren't sensitive enough (we can't hear the creaking of bees' knees).

When we turned the gain on our electric guitar up too high, we started to get strange sounds out. These sounds weren't just bigger versions of the input, they were distorted.

This happened because our signal got too loud for the poor little circuits in the amplifier. At a certain point, they're putting out the loudest sounds they can, and some of the details start to get lost.

Gains Applied to Gains

Imagine we put a microphone next to the amplifier. That microphone captures the sound, transmits it down a wire, and then puts the sound back out through another amplifier.

If that amplifier has a high gain, then we'll get a louder sound out of this amp than out of the first one. If the gain is 1, we get the same sound. If the gain is lower, we'll get something quieter.

Anyone who has actually worked sound is cringing at the above setup, and for good reason! Microphones tend to be quite sensitive, so they have large gains. If the microphone is close to the second amp, the sound that comes out of the second amp will go into the microphone, become louder thanks to the amp's gain, and then go into the microphone at a higher volume.

This process continues until the sounds coming out of the second amplifier are loud and totally incomprehensible.

Click the picture below to head to Youtube and watch this process in action with two iPhones acting as the microphones and amplifiers.

Neurons and Gains

So how does this all come back to neuroscience?

Neurons take signals in, just like the microphone or the pick-ups in our guitar. They also produce signals, just like our amplifier. That means we can think of them as having a gain†.

We also hook neurons up to other neurons, just like in our example with the two amplifiers. Let's consider what happens if we have a few neurons in a row, each with different gains.

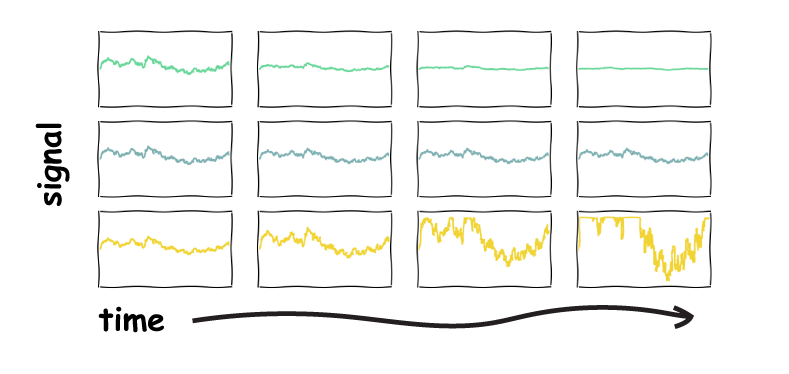

Each row is a group of neurons with different gains. The first column is the neuron that receives the initial signal. This neuron applies its gain and passes the signal to the neuron in the second column, which applies its gain and passes the signal to the neuron in the third column, and so on.

In the first row, all the neurons have a gain less than 1. Each time we pass the signal through a neuron, the signal gets "quieter". By the time we reach the final neuron, in the top right box, the signal has been totally lost.

In the last row, all the neurons have a gain greater than 1. Each time we pass the signal through a neuron, the signal gets "louder", until, just like the circuits in our amplifier, the neurons reach their maximum response (e.g. firing rate), and so they saturate. If you look at the signals on the bottom row, you can maybe understand why this phenomenon is called "clipping" in audio engineering.

The second row is the Goldilocks row. All the neurons have a gain of 1, so the signal is perfectly preserved as we pass through each neuron in turn.

Of course, with a real group of neurons, we'd want to do more than just copy the signal. The same principle applies though: we want to make sure the signal isn't continually increasing or decreasing in amplitude as we apply our transformations.

Homeostatic Plasticity

The growth of the signal amplitude as the signal goes through multiple layers of neurons is exponential – literally! The brain is also very deep – in fact, just like the amp and microphone setup, it feeds back into itself. You can think of this as meaning that the brain is "infinitely deep", from the perspective above, so even a tiny deviation from a gain of 1 would eventually lead to signal loss from quiescence or explosion.

The processes that we call homeostatic plasticity ensure that neither of those things happen. When a neuron's firing rate is lower than it expects, homeoplasticity engages to increase that rate. Vice versa for high firing rates.

If you're familiar with neurobiology, you can probably think of a million ways to achieve either of these goals.

As it turns out, the brain uses just about every tool at its disposal to ensure homeostasis through plasticity. Mark Bear and Robert Malenka called it "an embarrassment of riches", and discovering the complex links between all of these processes is a major research program in neuroscience.

If you'd like to learn more about plasticity mechanisms, which are also critical for learning, check out this post.

Footnotes

† You might, quite rightly, object that neurons transform their input, unlike our amplifier, so they're more like an effects pedal. For audio tech types: neurons are, at the very least, low-pass filters. Just look at the differential equations for a basic neuron model! This is a fair objection, but making neurons more complicated doesn't change anything about the rest of the argument: homeostasis is still critical. If you're not convinced, consider how hard neural network engineers work to make sure gain is controlled in their networks.