Answer

This prize was awarded in 1981, with 1/2 going to Sperry for his work on functional lateralization and 1/2 split between Hubel and Wiesel equally for their work on receptive field characterization in the visual cortex.

Hubel and Wiesel

The two key papers associated with Hubel and Wiesel's prizes (and names!) were released in 1959 and 1962, both in the Journal of Physiology. Since the 1962 paper is the subject of another post, this post will cover the 1959 paper.

These experiments pioneered single-cell sensory electrophysiology – the measurement of the response properties of individual neurons.

Videos from the experiments show the basic procedure: light stimuli are presented to an anesthetized cat, and the action potentials, or spikes, are recorded (audible in the video as pops and clicks).

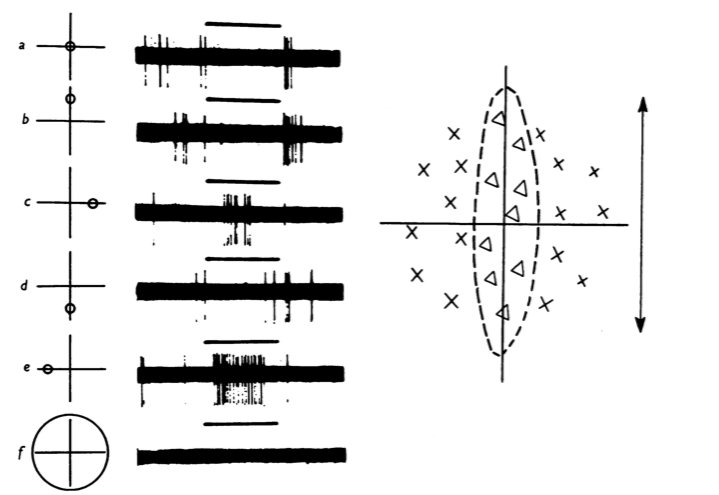

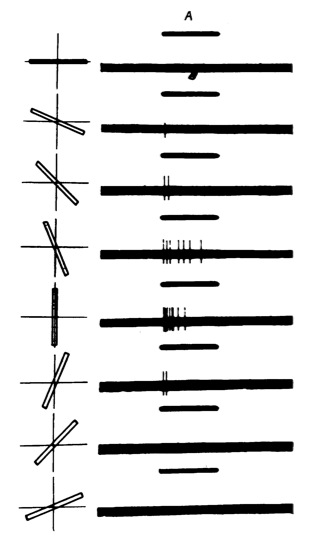

The first and second figures show the mapping of a receptive field, while the third show an orientation tuning curve. Both of these methods are now basic tools in neuroscience, and though they'd been applied in the retina by, e.g., Kuffler this paper represents their first application to cortical cells.

Fig. 1 The mapping of a V1 simple receptive field with dots of light. The receptive field appears on the right. Excitatory regions are marked with Xs, inhibitory regions with ∆s. The left half of the figure shows example extracellular recordings of action potentials, taken during stimulation of the region of the visual field indicated on the left-most axes. Stimulation periods are indicated with black bars.

Fig. 2 Figure 3A from Hubel and Wiesel's 1959 paper. Bars of light are presented at various orientations (left half), and the responses are shown on the right. Note that this cell has a preferred orientation, with the evoked firing rate decreasing as the orientation is varied. Observations like this were important for the development of the rate-coding hypothesis.

The cells represented in these figures are now called "simple cells".

Figures 4-6 dive into some more complicated cells, which would become the focus of their follow-up paper. These include a cell with a hemispheric receptive field and an extremely sensitive boundary detector, a motion- and orientation-sensitive cell, and a cell with two excitatory regions sandwiching an inhibitory region. Figure 8 shows another now-well-studied cell type, the direction-selective cell.

These findings would become the basis for their more in-depth 1962 paper, which includes a putative circuit mechanism for the construction of simple and some complex cells.

You can read a more focused and modern approach to the construction of these circuits in this blog post on the retina and this one on perceptual invariance.

Hubel and Wiesel received a Nobel for this work because it launched decades of neuroscientific inquiry into single unit cortical physiology. Many of the techniques pioneered here are still in use today.

However, the work was not without its flaws: it encouraged a linear, feedforward view of the brain that underestimates the complexity and the power of the non-linear, recurrent biology. The receptive fields they mapped were reduced to mathematically tractable stimuli, like Gabor functions and sine-wave gratings, which divorced sensory physiology from its ethological base, as represented by, e.g., Lettvin, Maturana, McCulloch, and Pitts in "What the Frog's Eye Tells the Frog's Brain".

Recently, there has been a move towards "natural stimuli", or images of the world, rather than the kinds of simple stimuli favored by neurophysiologists following in the footsteps of Hubel and Wiesel. Of course, the analyses performed on neural responses to these stimuli are impossible without modern computing power, and so were infeasible in the middle of the century.

The picture of the brain painted by these analyses is still being filled in, but my personal favorite is the "Hierarchical Bayesian Inference" approach of Tai Sing Lee and David Mumford. This approach makes good use of the complexity of the biology, and implies that even simple cells should be affected by context in ways unpredictable from their responses to bars alone. Perhaps this explains why, fifty years after Hubel and Wiesel, we still only understand what about 15% of V1 is doing.

A side note: if you want to read a sad story about genius, alcoholism, hubris, and star-cross'd fate, check out the story of Walter Pitts. There but for the grace of God.

Sperry

Roger Sperry primarily won the prize for his work with "split-brain" organisms. The two hemispheres of the brain are connected by a massive tract of white matter, the corpus callosum, or "tough body". Sperry, interested in the problem of how learning was transfered across sides of the body, cut the corpora callosa of cats and monkeys and demonstrated that subjects sometimes behaved as if they had "two brains": a task learned with only one eye open did not transfer to the other eye.

Sperry is more famous for the work he did with humans to follow up on this work. Since invasive surgical insults are not an acceptable human subject protocol, Sperry made use of patients with spreading epilepsy. In these patients, the corpus callosum had been severed to stem the flow of epileptic waves. In fact, Sperry's experiments with split-brain animals had led to development of this (now-obsolete) surgical cure for epilepsy.

In a series of experiments, Sperry showed that the function of language was lateralized – only the left hemisphere was capable of viewing a stimulus and generating appropritate linguistic responses. The right hemisphere was capable of concept association, but not of verbalization. Work in this field eventually demonstrated that humans don't have conscious access to their right hemisphere, and will confabulate, or generate false explanations, when asked about right-hemisphere-driven behavior.

Though much of this work was invaluable for demonstrating functional specialization and lateralization in the brain, it unfortunately spawned a cottage industry of bad science, drawn to the ontological binary of "logical left brain" and "creative right brain" like moths to a flame. This distinction, like the Myer-Briggs personality schema (are you an introvert or an extrovert?, etc.) and the theory of learning styles (are you a visual learner or a haptic learner?) is more emotionally satisfying than it is evidence-based.

And one can certainly hold Sperry accountable for this. In his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize, he said: