Answer

In this post, I focus on two specific mechanisms representing two classes: regulation of the precursor cell and regulation of the offspring cells.

As an example of regulation of the precursor cell, we consider the cell division of the radial glia, which gives rise to the cortical excitatory pyramidal neurons. As an example of regulation of the target cells, we consider the organization of these same cells into the six neocortical layers.

The Big Picture

In some sense, a correct answer to this question would be "every mechanism in development".

This is because developmental neurobiology is the study of how one cell, the zygote, gives rise to a whole organism. In a very real sense, the humble zygote is the precursor cell to all the cells in your body.

Of course, this is about as informative as saying that bacteria-like organisms are the ancestors of all life on earth. Just as your great-great-…-grandmother was a monkey, the zygote is the great-great-…-grandcell of your kidney cells, your muscle cells, etc.

This question is really asking about direct precursors: the "parents" of a cell.

With that in mind, let's look at two mechanisms the lead to different cell fates for "siblings", or offspring of the same cell.

Precursor-Based: Radial Glia

Besides playing a variety of important roles in the developed brain, including myelination, forming the blood-brain-barrer, neurotransmitter reuptake, the neurovascular response, and possibly even computation, the quote-unquote auxiliary cells known as "glia" are also critical for the development of the cortical pyramidal neurons who, ungratefully, steal their spotlight. Life's not fair.

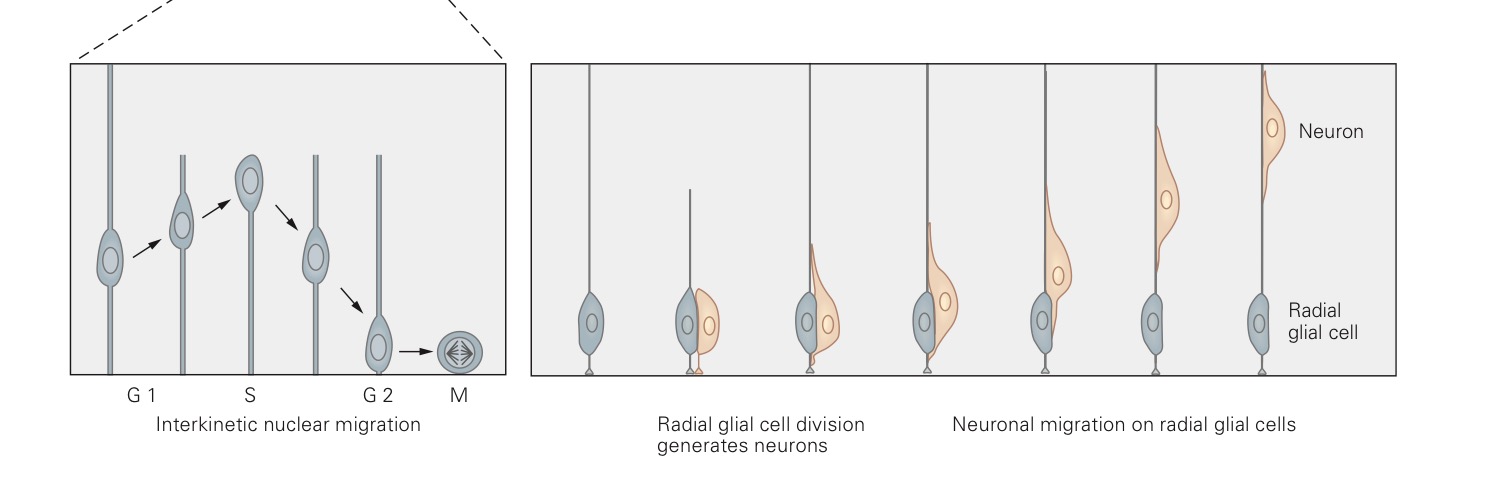

The radial glia are the first cells to appear in the developing cortex. They appear at a time when the brain looks a bit like a tube of cells filled with liquid – the cerebrospinal fluid. Their cell bodies are close to the fluid side, but they extend long, thing processes out towards the outer edge of the tube, much like the spines of a chinese fan.

These cells are continually dividing, sometimes dividing into two radial glial cells, sometimes dividing into one radial glial cell and one neuron. In the latter case, the neuron then climbs up the long spine of the radial glial cell, off on its merry way to become a cortical neuron, as described in the second half of this blog post.

The resulting radial glial cell then serves as a precursor to more cells. Sometimes the next division is also asymmetric, i.e. resulting in a neuron and a precursor, and sometimes it is symmetric, i.e. resulting in two precursors.

The picture below, adapted from Figure 53-2 in the 5th edition of Kandel and Schwartz, shows both of these processes, symmetric on the left, asymmetric on the right.

So what gives? How do the offspring of a precursor "decide" whether to be neurons or precursors?

The key is, surprisingly, the orientation of the plane of cell division! When the cells undergo mitosis, they split in half, with the dividing line determined randomly at each division.

Sometimes that line is parallel to the glial process, and sometimes the line is perpendicular to it.

Now, the plane of cell division is random for every dividing cell in the body, but it usually doesn't have any effect on the offspring cells.

But in this case, it does, thanks to a protein called Notch that collects at the bottom of the cell, like a sediment.

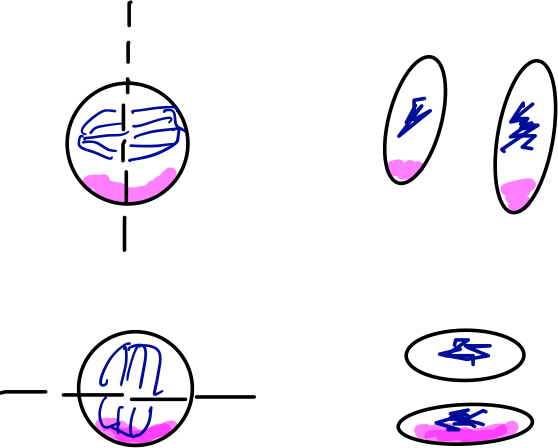

The processes of symmetric and asymmetric division appear below, with the parent cell on the left and the offspring on the right.

In blue, we see the DNA of the cell, busy replicating itself and then getting dragged to one end of the cell or the other by the mitotic spindle. I've drawn the plane of division in black. In pink, we see the aggregated Notch protein.

In the division event on top of the image, the plane of division goes parallel to the glial process (not pictured), perpendicular to the surface on which the cell rests. This results in two cells with equal concentrations of Notch. Both cells go on to become precursors.

In the division event on the bottom of the image, the plane of division goes perpendicular to the glial process, therefore parallel to the surface on which the cell rests. This results in two cells with unequal concentrations of Notch. The cell with more Notch becomes a precursor, while the cell with less Notch becomes a neuron.

This mechanism for generating different offspring from a single precursor relies on a mechanism inside the precursor cell itself.

More commonly, external signals acting on the offspring determine the cell fate. We turn to this case now.

Offspring-Based: Cortical Layers

Examples of offspring-based mechanisms abound. One could coherently argue that, for example, differentiation in the spinal cord or even axon guidance serve as examples of this phenomenon.

For the sake of covering additional material, I'll be prosaic and look at a more classical example of environmental influence on cell fate: the differentiation of the cortical layers.

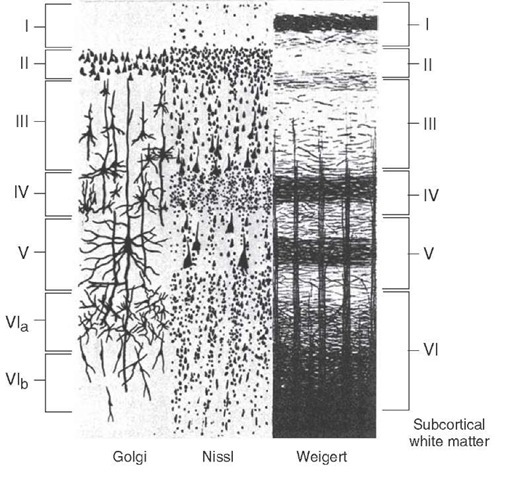

To start with: the mammalian neocortex is composed of six layers, creatively named layers I, II, III, IV, V, and VI. These layers are labeled from the outside in. Each layer is functionally distinct: input from the senses arrives in IV, for example, and output to other cortical regions comes from II/III. They are also anatomically distinct, as you can see from the diagram below, which shows what the six layers look like under three different stains, which show, respectively, a few cells in their entirety, most cell bodies (aka grey matter), and most myelinated processes (aka white matter).

From what-when-how.

All of these neurons arise from genetically identical precursors, the radial glial cells of the first half of this post, and yet they end up in different places and with different shapes. We ask again: what gives?

In this system, nurture wins out over nature: the environment determines cell fate, rather than the circumstances of birth, as in the division of radial glia.

That is, the biochemical environment into which the newborn neurons travel as they clamber up the radial glia changes over time, leading these identical cells to experience different environments.

This temporal mechanism for determining cell layer identity leads to a temporal progression in the development of the layers: layer VI forms first, then layer V, and so on, up to layer II. Layer I, as can be gleaned from the above diagrams, is a special case, since it contains very few cell bodies.